Walter Isaacson:

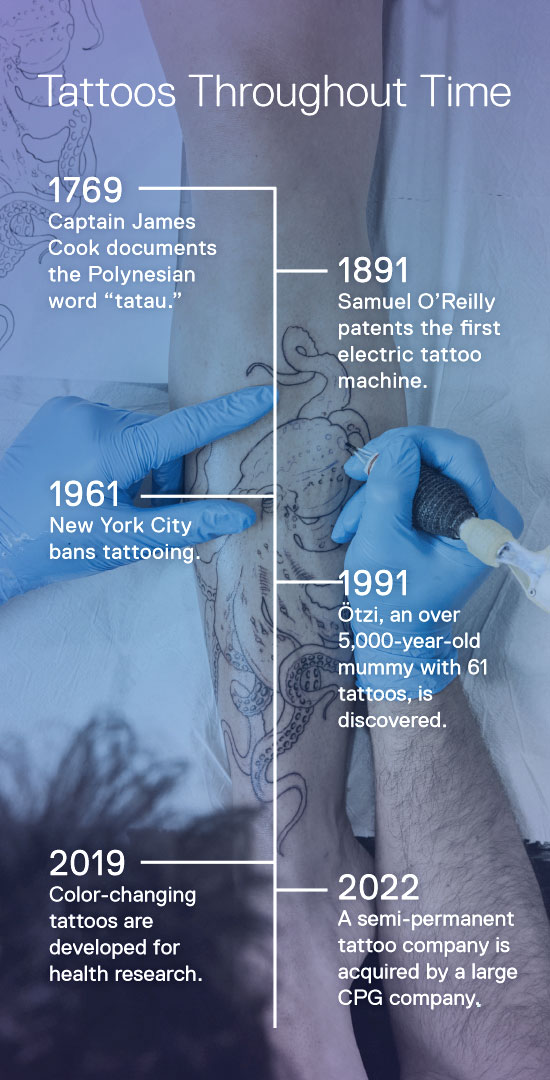

It’s September 19th, 1991, and two German tourists are enjoying a scenic hike high up in the Ötztal Alps, near the Italian/Austrian border, when their afternoon takes a very unexpected turn. While skirting the edge of a receding glacier, they stumble upon a human body protruding from the ice. Assuming it’s a recent mountaineering fatality, the hikers notify the Austrian authorities. Five days later the body is extracted from the ice with pickaxes and a jackhammer, but when the body lands in the morgue, it becomes clear this death was anything but recent, and it was certainly no accident.

Walter Isaacson:

Closer inspection of the body, named Ötzi, after the mountain range where it was found, suggests that the cause of death was a single arrow to the shoulder, and tissue samples indicate that it’s more than 5000 years old. Even more interesting than Ötzi’s age or cause of death is what archeologists find on his mummified skin. Ötzi is sporting 61 tattoos.

Walter Isaacson:

The tattoos are clusters of black lines on different parts of the body, including his ankles, wrists, knees and lower back. Because Ötzi’s tattoos are in locations intriguingly close to modern acupuncture points, it’s thought that they were a form of physical therapy. In fact, scientists theorize that most ancient tattoos had a practical or medicinal purpose. It’s believed that they denoted ones tribal rank, or in the case of Ötzi, a form of pain management.

Walter Isaacson:

The discovery of Ötzi the ice man is one of the greatest archeological finds of the 20th century. It’s given researchers an unprecedented look at life during the Bronze Age, and, although the exact meaning of Ötzi’s tattoos remains a mystery, it’s one of the earliest examples of body ink.

Walter Isaacson:

Today, tattoos have evolved into a deeply personal and artistic form of body modification. It’s an art form that’s become an industry. Americans alone spend about $1.6 billion a year on tattoos. In fact, 46% of Americans are inked, making the US the third most tattooed nation in the world, behind Italy and Sweden. Today, even as tattoo artists continue to amaze with the artistry they express on the human canvas, the field’s brightest innovators are still expanding what’s possible with new inks, enhanced tools, and limitless imagination.

Walter Isaacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson, and this is Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Chuck Eldridge:

The circus world for tattooists go back to the 1800s.

Shanghai Kate:

I have letter from Sailor Jerry, inviting me to open a tattoo shop with him.

Omar Fame Gonzalez:

I’m known for all kinds of style, color, black and gray, realism.

David Fernandez Rivas:

We need a tattoo artist to think about the way that we modify our bodies.

Katia Vega:

I think it’s very valuable when the tattoo has a meaning.

Walter Isaacson:

Evidence of tattooing can be found all over the world in the remains of many early indigenous cultures, but until somewhat recently tattooing was an unknown practice through most of Europe. That started to change in the 18th century, when sailors, fascinated by the body art they encountered on their voyages, brought tattoos home with them on their bodies.

Chuck Eldridge:

Not just sailors, but people when they travel, they always want to bring back some souvenir from that travel.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Chuck Eldridge. He’s a tattoo artist and founder of The Tattoo Archive.

Chuck Eldridge:

These natives had been tattooing for centuries. I’m sure the sailors were fascinated by that, and so they would get tattooed, and that would be the souvenir that they would bring back. Often those sailors that were tattooed on those voyages would become tattooers themselves. Sometimes there would be a tattooer aboard ship and they would tattoo the men for money or cigarettes, or for their rum ration or whatever, and so other artistically inclined sailors would go, “Whoa, I think I could do that.” The next port they would be looking for some needles and some pigment, and they would start tattooing themselves.

Walter Isaacson:

Once they left the Navy, these artistically inclined and business savvy sailors became professional tattooists in the towns where they had settled.

Walter Isaacson:

Stylistically, these early tattoos were not realistic or complex. Made with black ink poked into the skin using a single needle, artists created images with simple lines. Most tattoos had a nautical theme layered with the deeper meaning of a sailor’s life. The most common, an anchor, represented stability and was most often adorned with the word mom. Five pointed nautical stars led sailors home safely, while hearts reminded them of loved ones waiting for their safe return. Other images signified a sailor’s time at sea. A swallow represented 5000 miles of travel, and only sailors who crossed the equator earned the right to sport a turtle.

Walter Isaacson:

Even with these honest themes, most land loving Europeans did not embrace this new art form. A tattoo’s air of risk attracted those living on the fringe of society, and the practice quickly became associated with criminals and women of ill repute. Religious leaders denounced tattoos, pointing to the Bible to justify their disapproval.

Chuck Eldridge:

Well, the bad reputation for tattooing is I think eternal, to be truthful, but I think a lot of it goes back to the Bible and Christianity and religion. The Bible, Leviticus talks about not marking the body, so when people read that, they think tattoos. They don’t want any tattoo marks on the body. That is kind of a stumbling block, that has been a stumbling block for tattooing being accepted.

Walter Isaacson:

Its bad reputation didn’t stop tattooists from searching for a way to improve their trade. In 1876, Thomas Edison invented a device that helped them to do just that. His machine was a small handheld tool that helped duplicate important letters. It was the prototype tattoo artists needed to mechanize their craft, but it wasn’t until 1891, when a tattoo artist named Samuel O’Reilly patented an adaptation of Edison’s handheld design that it officially went to market.

Chuck Eldridge:

They were called rotary machines because they would have a big wheel that would rotate, and then that would be connected to a kind of device that would transfer that rotary motion into a reciprocating motion so that the need basically just moved up and downward. That was in a handheld device that you could manipulate over the skin and push pigment in.

Walter Isaacson:

These early machines not only increased the speed of tattooing, they also gave artists more control over the depth and force of application. This led to the more precise art form that we know today.

Walter Isaacson:

In the early 1900s, this machine allowed artists to create new designs that were so intricate and captivating that the general public was willing to line up and pay to look at them.

Chuck Eldridge:

Well, Amund Dietzel was Danish. He was a merchant seaman and was shipwrecked in Canada. He tattooed a little bit in Canada. He had those skills with him from aboard ship. He was a classic tattooing sailor.

Walter Isaacson:

Dietzel made his way south through Eastern Canada, eventually landing in the US. Here his fully tattooed body earned him a job as the tattooed man in circus side shows. After his act, he would set up a small table and, for a fee, tattoo curios audience members.

Chuck Eldridge:

Those designs and those imagery that was popular in Europe just kind of transferred right over to America. I mean, a lot of those designs, all they really needed to do was change the flag on the ship designs, and the anchor designs, and the eagle designs. They had European flags. They just put an American flag and the design just crossed right over and worked perfect in an American shop. It is ironic that after the natives had tattooed in North America for centuries that it was European immigrants that brought professional tattooing to the states.

Walter Isaacson:

Dietzel and other side show circus acts like him helped push the art of tattooing inland, beyond port cities, into rural communities, but it wasn’t until World War II that tattooing made its big push into middle America. It was during this time that a legendary tattoo artist rose to prominence in the US. His name was Sailor Jerry.

Chuck Eldridge:

His tattoos were taking kind of the traditional idea, but giving them just a little twist, just a little tweak that made them kind of unique. I mean, you see Sailor Jerry tattooing and you kind of begin to recognize it. It was very bold, very graphic, very colorful. Strong, is how I think I would describe it best.

Walter Isaacson:

Born Norman Keith Collins, Sailor Jerry settled in Hawaii in 1930 to set up a tattoo shop after a stint in the Navy. A little over a decade later, Pearl Harbor was attacked. Suddenly, the US was at war and thousands of soldiers were on shore leave in Honolulu. The youth, bravado and fear of death that Sailor Jerry saw in these American servicemen became a deep thread in his art. His colorful images of pinup girls, dice and dollars signs, juxtaposed with hearts, anchors, and odes to mothers, remain iconic to this day. Ironically, Jerry also became influenced by the culture of the country that bombed Pearl Harbor, Japan. Sailor Jerry studied the Japanese tattoo masters, becoming the first westerner to fuse American and Asian artistic sensibilities. Through this merger, he created his own art form, beautiful and wildly stylized images that have influenced generations of tattoo artists that came after him.

Shanghai Kate:

They know me as Shanghai Kate.

Walter Isaacson:

Shanghai Kate, an apprentice of Sailor Jerry, is known as the godmother of American tattooing, but as a female tattoo artist in 1971, her route to acclaim wasn’t easy. Even her invitation to apprentice under Sailor Jerry was less than conventional. In fact, the invitation involved an altercation between two of Sailor Jerry’s other proteges.

Shanghai Kate:

Michael Malone and Ed Hardy got in a fistfight over me in Sailor Jerry’s front yard. I said, “I’m not going home with either one of you guys.” We had come from San Diego to do the conference at Sailor Jerry’s house, and Jerry said, “Well, you can stay and work with me.” I said, “I’m staying and working with Sailor Jerry.”

Walter Isaacson:

It was a moment that changed the trajectory of Shanghai Kate’s life forever.

Shanghai Kate:

He was an old salt. He had been everywhere. He knew everything, and he defined tattooing from the ground up. I looked to him as a father more than anything, and a great teacher, and I cherish every moment that I ever spent with him.

Walter Isaacson:

Sailor Jerry was building his legacy well before he met Kate. In 1961, in reaction to a hepatitis outbreak that prompted New York City to ban tattooing, he became a vocal advocate for enhanced sterilization.

Shanghai Kate:

The man who wanted to open a tattoo shop in New York City and couldn’t because it was banned, Jerry said, “We’ve got to start sterilizing, because if they can close New York City, they can close the country.” He brought sterilization into the industry. Sailor Jerry taught me everything about sterilization, which is really how to be absolutely meticulous in your cleanliness, that hospital style sterilization that you have to adhere to in order not to pass any kind of blood disease.

Walter Isaacson:

Reducing the spread of blood borne diseases was not Sailor Jerry’s only cause. Famous for his colorful tattoos, he was also on a constant search for an expanded pallette of safe tattoo pigments and ink.

Shanghai Kate:

Well, the first four colors were black, red, yellow and green. The red, yellow and green were laced with mercury, so mercury poisoning was just everywhere in our industry. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen mercury poisoning under the skin, but it’s really horrible.

Walter Isaacson:

It was a quest that Sailor Jerry and Shanghai Kate tackled together. Pretending to be sign painters, they were able to get pigment samples from companies that wanted nothing to do with the underground art of tattooing.

Shanghai Kate:

I wrote to them and said, “Would you send us samples of your dry pigments in little packages so that we could test them for sun worthiness for our signs?” We would get these little packages of dried pigment, and then we would put them in the skin and we would sit back, and if it reacted, say for a mercury content, they would dig it out. Jerry did it with a flathead screwdriver, he didn’t care. That’s how we got the colors that are nonreactive to the human body with mercury.

Walter Isaacson:

Perhaps most famously, Sailor Jerry was the first tattoo artist to create purple ink from a blend of these new, safer pigments. If it wasn’t Sailor Jerry changing the industry, it was usually one of his proteges. Ed Hardy eventually moved away from standardized tattoos by doing something revolutionary. He asked clients to suggest images that meant something to them. Today, getting a tattoo that represents who you are may seem commonplace, but it was a radical departure from other tattoo studios in the 1970s.

Shanghai Kate:

He’s always tried to expand the horizon of the imagery that people get, and they should get their dreams. They should get their choices of their inner body on their outer body. Yes, he started that. One of Ed’s primary slogans was wear your dreams. He’s done really well. He’s an incredible artist.

Walter Isaacson:

While personalization began to pull tattooing closer to the mainstream, it was the introduction of MTV in 1981 that made the art form a pop culture fixture. Suddenly, tattooed rock stars and celebrities were in people’s living rooms. This helped normalize the art form for a curious, but still slightly wary audience. Then in 1997, New York politicians surrendered to public pressure and lifted the ban on tattooing. As tattoo artists emerged from their underground parlors, Kate was pleased to see that many of them were women.

Shanghai Kate:

I went to a tattoo convention and every booth was filled with women, and I take some credit for that because nobody saw women in tattoo booths before I came along. I’m very honored. They cry. They come up to me and cry. They thank me so much, and they give me presents. They do honor me, and I’m very grateful. I think that I did a good job.

Walter Isaacson:

Suddenly, tattooing’s new profile and wider acceptance turned the craft into a viable and lucrative profession for a new generation of artists. Much like the older generation, many new tattooists rely on apprenticeships to learn their craft. Unlike pioneers, such as Sailor Jerry and Shanghai Kate, they also have a new way to trade techniques and inspiration, social media.

Omar Fame Gonzalez:

When Myspace came out, this was years ago, that’s when I started really seeing the art around the world and what people are able to accomplish with tattooing.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Omar Fame Gonzalez, the owner of Fame Tattoos in Miami, Florida.

Omar Fame Gonzalez:

I had a certain vision of tattooing at that time, this was over 20 years ago, and I actually got more love for the art of it. I started looking at different artists, started researching websites of artists. There was different platforms back then to look at artists from around the world, and that’s how I started getting inspired by everybody else’s work.

Walter Isaacson:

Over the last decade, social media has helped tattooing cross pollinate with other art forms, which has brought new techniques and styles to the industry. There are few new techniques as visually gripping as Gonzalez’s 3D x-ray tattoo.

Omar Fame Gonzalez:

When you look at the 3D x-ray tattoo, you actually look at one image at first glance, which is multiple colors. You see part of the outline of the character and then you see a skeleton, but when you put on your 3D glasses, which is the red and blue lens, you look through one lens, which is the red, and you see a certain style, probably the skeleton. Then when you go with the blue one, you see the whole body. People have a ball with it, they trip out when they see it. They’re like, “How is this possible? Is this chemical ink? Is it dangerous?” I’m like, no, it’s regular ink. It’s the same ink that everybody has, it’s just certain colors that I’ve mixed and formulated so it could be the right colors that work with each other.

Walter Isaacson:

Gonzalez’s inspiration came from a graffiti artist he found on Instagram named Insane 51. The artist created a giant mural of a beautiful woman whose skeleton was faintly visible, as if a picture of her x-ray had been superimposed on her portrait. Gonzalez set out to recreate it as a tattoo. First, he experimented with a design using Photoshop. Then Gonzalez found a tattoo artist willing to let him practice a small scale version of his 3D tattoo on their skin. When Gonzalez achieved the look he wanted, he pitched the tattoo to a customer as a large back piece.

Omar Fame Gonzalez:

He let me. He was like, “Go ahead. Do what you got to do.” The first session I worked on the lower back, and when I was done I put the glasses on and I’m like, wow, this is going to work.

Walter Isaacson:

Luckily, it did work, and led to a very satisfied customer.

Omar Fame Gonzalez:

He loved it. He loved that back piece. We’ve won multiple awards with it. Every time we go to a tattoo convention, he walks around without a shirt and everybody’s like, “You’re that guy. You’re that guy that has that crazy back piece.” It’s cool to go into a tattoo convention and people come up to me and be like, “You’re that guy that recreated a tattoo.”

Walter Isaacson:

While artists such as Gonzalez continue to push the limits of what’s possible with tattoos, scientists are working to improve on Samuel O’Reilly’s electric tattoo machine.

David Fernandez Rivas:

My name is David Fernandez Rivas, and I am a professor at the University of Trenton, and affiliate to the Mechanical Department Engineering at MIT.

Walter Isaacson:

Fernandez Rivas and his team have created a needle free injection tool they call the bubble gun. This device uses a laser to heat liquids until bubbles start to form. Then the expanding bubbles push the liquid through a very small channel at speeds fast enough to penetrate the skin. Research into the bubble gun began in hopes of modernizing medical injections, but Fernandez Rivas soon realized there was another industry that might be interested in needle free injections.

David Fernandez Rivas:

When we started doing this sort of exploratory research to find out who else has been trying to inject small volumes superficially into the skin, and we came to the conclusion that sounded very similar to tattooing. We first went out to the streets and started talking to tattoo artists, people who have got tattoos themselves. They show me all the different tools they were using, the type of needles, their procedures, and then I start learning the art and the craftsmanship that this entails.

Walter Isaacson:

Not only did they learn that traditional tattoo machines waste up to 50% of the ink, but the quick in and out motion of the needles can be quite painful and damaging to the skin.

David Fernandez Rivas:

This, from an engineering point of view, I said, “If we can make this art safer and less damaging for the skin of the people, then this can be even a market opportunity for tattoo artists.” It’s not an idea to replace all type of needles, but they see that their customers that leave the shop even before the first needle hits their body because they afraid of needles.

Walter Isaacson:

For needle phobic customers, which is roughly 25% of the population, the bubble gun could be a revolutionary new tool that helps them finally get inked, but that’s not the only good news for those thinking about getting a tattoo.

David Fernandez Rivas:

The way we are creating these droplets is very interesting because the volumes are so small and the velocities we’re using are in a range that in tests that we have done in the lab and asking experts in pain and also dermatologists, it’s almost impossible that we heat the skin in a way that people would feel it.

Walter Isaacson:

It’s not only the absence of needles that’s getting the attention of tattoo artists, it’s the bubble gun’s potential to be completely pain free.

David Fernandez Rivas:

When you’re an artist, for example a painter, he probably has an array of brushes, and for specific parts of the canvas he probably uses a different type of brush. My message will be, this is an addition to the toolbox that tattoo artists have. Because it can expand their opportunities or the ways where they can bring the art or transfer the wishes of their customers into the skin in a safer and painless manner.

Walter Isaacson:

As Fernandez Rivas and his team create waste free and painless ways to get inked, other researchers are revolutionizing the ink itself.

Katia Vega:

If you think about pregnancy tests, they change color, we could see tattoos kind of like a very similar way.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Katia Vega, Director of the Interactive Organisms Lab at UC Davis.

Katia Vega:

There are these biosensors that will be, in this case it’s liquid material, that we will be changing the color depending of different levels that you want to analyze of your body.

Walter Isaacson:

These biosensors are liquids that pick up information about our health. When they come in contact with the interstitial fluid in our skin, they change color accordingly.

Katia Vega:

The interstitial fluids are these fluids that are fascinating, that are already going around our dermis. It already carry a lot of information from ourselves, so then as we were introduced to biosensors, and we were also understanding more how the skin works and how the interstitial fluids work, we put these things together and, wow, it will actually make tattoos that are not static in color, and they could react with these fluids that we have inside of our skin.

Walter Isaacson:

Deposited into a patient’s skin as a tattoo, biosensors are potentially life changing science for people such as diabetics, who need to monitor their glucose levels.

Katia Vega:

Not just one glucose sensor. We could also incorporate a Ph sensor. We could incorporate a sodium sensor. That for us was very interesting, because for continuously monitoring an illness, it’s not based in just one anolyte. Having a tattoo like, let’s say imagine a flower, and one petal is one color and the other one is another one, the other one is another one, and each of them is revealing information. That’s was what we thought we wanted to share and express with this project.

Walter Isaacson:

Vega hopes to eventually marry art and medicine by empowering patients to incorporate the specific biosensors they need into body art that resonates with them on a personal level. Perhaps one day these biosensors will be used to ink people without medical conditions, who simply want to express themselves with body art that can change color.

Katia Vega:

I feel like that also gives us that open space to think about the way that we modify our bodies. There are all these differing artists and how they will be the ones that will have that expertise and could be incorporating biosensors that changes color into their own designs.

Walter Isaacson:

With this amazing innovation, we come full circle, back to Ötzi, the ice man, whose ancient tattoos were etched with the hope of healing his body. Whether a tattoo is an homage to life at sea, an ode to mother, a 3D woman, or a medical necessity transformed into art, tattoos are and will always be a deeply personal expression of our individuality. Chuck Eldridge.

Chuck Eldridge:

I find tattooing just fascinating. The whole art of it, the fact that it’s on your skin, that you carry it with you. It’s something that you can’t lose. It speaks about who you are. It’s just a fascinating art form that back in the day was kind of an outsider art form, and I kind of like that too.

Walter Isaacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson, and you’ve been listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies, who believe there’s an innovator in all of us. If you’d like to learn more about the guests on today’s episode, please visit DellTechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

CW Eldridge

In 1978, Eldrdige started learning the art of tattooing from the famed tattoo artist Ed Hardy at his original Tattoo City in San Francisco. Several years later, Eldridge founded the Tattoo Archive in Berkeley, California where he has been documenting the history of tattooing for over 40 years.

CW Eldridge

In 1978, Eldrdige started learning the art of tattooing from the famed tattoo artist Ed Hardy at his original Tattoo City in San Francisco. Several years later, Eldridge founded the Tattoo Archive in Berkeley, California where he has been documenting the history of tattooing for over 40 years.

David Fernandez-Rivas

is an engineer, scientist, educator, and co-founder of BuBclean and FlowBeams, spin-offs from the University of Twente. He focuses on teaching and solving societal challenges as Professor at the University of Twente and Research affiliate at MIT. He leads the BuBble Gun project, aimed at developing a needle-free injection method.

David Fernandez-Rivas

is an engineer, scientist, educator, and co-founder of BuBclean and FlowBeams, spin-offs from the University of Twente. He focuses on teaching and solving societal challenges as Professor at the University of Twente and Research affiliate at MIT. He leads the BuBble Gun project, aimed at developing a needle-free injection method.

Katia Vega

is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Design at the University of California, Davis, where she founded and directs the Interactive Organisms Lab. Her research tackles new explorations of organisms-device symbiosis including ink for tattoos can change colour.

Katia Vega

is an Assistant Professor of the Department of Design at the University of California, Davis, where she founded and directs the Interactive Organisms Lab. Her research tackles new explorations of organisms-device symbiosis including ink for tattoos can change colour.

Omar "Fame" Gonzalez

is an award-winning tattoo artist, born and raised in Miami, Florida. He is the co-owner of Fame Tattoos in Miami. Omar has been tattooing since 2003 and specializes in hyperrealism, from black and grey to color tattoos. He is best known for creating the Realism 3-D X-Ray Tattoo style. This style is incredibly unique and changes depending on the lighting, giving you three tattoos in one.

Omar "Fame" Gonzalez

is an award-winning tattoo artist, born and raised in Miami, Florida. He is the co-owner of Fame Tattoos in Miami. Omar has been tattooing since 2003 and specializes in hyperrealism, from black and grey to color tattoos. He is best known for creating the Realism 3-D X-Ray Tattoo style. This style is incredibly unique and changes depending on the lighting, giving you three tattoos in one.

Shanghai Kate

is the Godmother of American tattooing. She’s been a tattooist for over 50 years and apprenticed under the famed artist Sailor Jerry.

Shanghai Kate

is the Godmother of American tattooing. She’s been a tattooist for over 50 years and apprenticed under the famed artist Sailor Jerry.