Walter Issacson:

It’s September 25th, 1970, and Vice President Spiro Agnew is addressing a boisterous crowd in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Agnew is a staunch supporter of the Vietnam War. So the anti-war message championed by the youthful hippie movement of the time predictably does not resonate with him. In fact, Agnew believes one man bears responsibility for the disobedience of this flower power generation.

Walter Issacson:

During the speech, Agnew proclaims…”Who do you suppose is the blame when 10 years later that child comes home from college and sits down at the table with dirty bare feet and a disorderly face full of hair?”

Walter Issacson:

Agnew isn’t referring to an outspoken musician or political opponent. The man he’s denouncing is a pediatrician by the name of Dr. Benjamin Spock.

Walter Issacson:

In the early 20th century, doctors instructed parents to not pick up their babies when they were crying or show them too much affection. It was thought that this rigid approach to parenting would result in more resilient and independent children. Dr. Spock disagreed. So in 1946, Dr. Spock authored The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care.

Walter Issacson:

In his book, Spock advocates that while structure and discipline are important, parents also need to follow their instincts, be flexible and show their children love and affection.

Walter Issacson:

It was an instant bestseller and completely flipped the script on parenting.

Walter Issacson:

But by the 1960s, conservative personalities and publications all across the US were pushing back. They claim that the rebellious nature of the anti-war protestors stem from Spock’s “permissive ideas on parenting.”

Walter Issacson:

But his critics didn’t stop him. In 1976 The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care became the best-selling book of all time in the US, second only to the Bible.

Walter Issacson:

Dr. Spock changed our understanding of parenting and child development. But today, parents are raising their kids in a much more technologically complex world. So the question becomes how do parents use technology to help raise their children without letting it get in the way.

Walter Issacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson, and you’re listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Child:

Where to babies come from anyhow?

Adults speakers:

Our understanding and sensitivity can help so much.

Adults speakers:

Watching your baby grow stronger with those first few steps.

Adults speakers:

Yes, Mother, Junior remembered to clean up.

Adults speakers:

On your answers may well depend the physical and emotional health of future generations.

Walter Issacson:

You’ve probably heard the proverb, it takes a village to raise a child. When it comes to raising children, parents can’t do it alone. And for most of human history, they didn’t have to.

Jennifer Traig:

Parenting is a very recent term. It only dates until the 1970s.

Walter Issacson:

Jennifer Traig is the author of Act Natural, a Cultural History of Misadventures in Parenting.

Jennifer Traig:

Before that it was called childrearing. And the reason it wasn’t called parenting is because often parents weren’t the ones doing it. That task fell to other family members, often to older siblings, to the larger community, but not necessarily to the parents who had their hands full just trying to keep the family alive.

Walter Issacson:

The village that raised the child was an actual community all around us. We humans rarely left our childrearing village, and it rarely left us.

Walter Issacson:

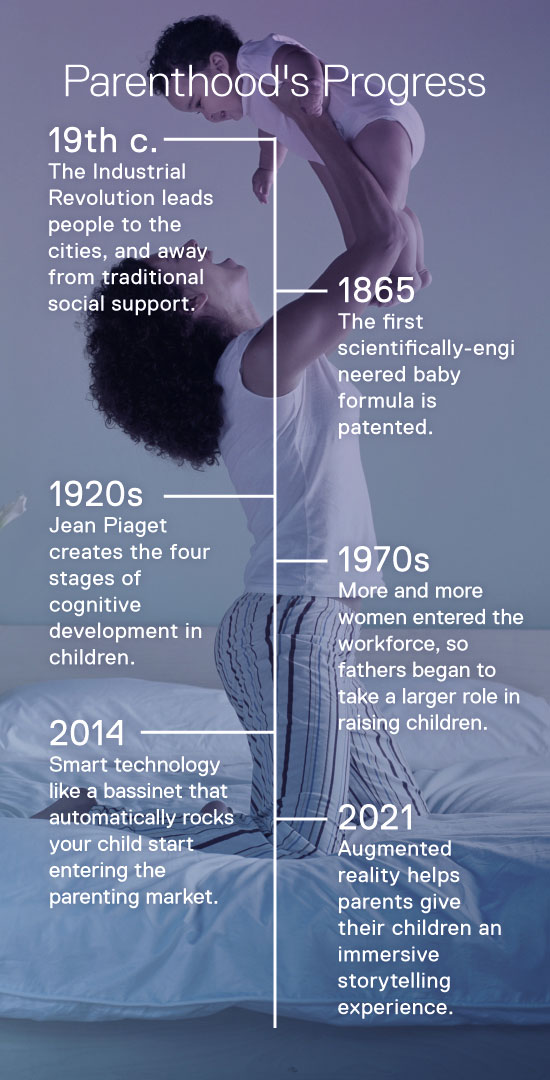

But that started to change in the mid 19th century. The industrial revolution led to a mass migration from the countryside to cities, and young families had very little social support when they got there. Orphanages were overcrowded. Many women died during childbirth, and many more had difficulty producing breast milk. By the 1860s, as many as one third of all babies who couldn’t access breast milk died before their first birthday.

Walter Issacson:

So German scientist Justus von Liebig decided to try to do something about it.

Jennifer Traig:

So Justus von Liebig was a chemist whose own children had trouble breastfeeding. And so he started to formulate a substitute for them.

Walter Issacson:

Von Liebig was one of the leading organic chemists of the day. He pioneered modern technologies and fertilizer and farming to help Europe grow more food to match its booming population.

Walter Issacson:

Next he decided to devote himself to solving the infant food crisis.

Jennifer Traig:

And what he came up with was a blend milk, of flour, of malt and potassium carbonate. It was sold as a liquid, and later it was sold as a powder. It was sold in pharmacies. This was in the early days of nutrition. It was missing a lot of things that kids needed. It was essentially what you have left in the bowl of cereal. It was cereal milk. So it was milk flavored with sugar and a little bit of starch.

Walter Issacson:

In 1865, von Liebig patented what he called his soluble food for babies. It was the world’s first scientifically engineered baby formula. It might not have been the perfect food, but it immediately made an impact, saving countless babies from starvation.

Walter Issacson:

A few decades later, in the 1920s, standards for childhood cognitive and physical development were introduced.

Jennifer Traig:

Suddenly there were timetables for every stage of development. And if you did not meet them, also for the first time, you would be blamed. This made no parent feel better. It was incredibly anxiety-inducing because it suddenly introduced benchmarks that you had to meet.

Walter Issacson:

At best, these schedules gave mothers a peg to hang their anxieties on. At worst, it caused them to distrust their own instincts and lose confidence in their parenting abilities.

Walter Issacson:

But what these well-meaning scientists created was a framework for modern parenting.

Alison Gopnik:

There’s a real difference between being a parent and parenting.

Walter Issacson:

Alison Gopnik is a professor of psychology and philosophy at the University of California at Berkeley.

Alison Gopnik:

The idea behind parenting is that there’s this goal-directed activity that you engage in sort of like all the other kinds of work that we do. Now it’s never quite clear what it is that the goal is, but basically the goal is that if we are parenting the right way, we’re going to end up with a child who is, in some ways, a better adult than they would have been otherwise.

Walter Issacson:

It was against this backdrop of goal-driven child development that Benjamin Spock created his alternative theory of parenting. This was especially important after the Second World War when another mass migration occurred, but this time people were moving from the cities to the suburbs.

Alison Gopnik:

Until just this very, very, very recent period, people were immersed in caregiving, and they learned it the way that you learn any kind of skill that you’re immersed in. And then what started to happen was as families became more mobile, as there was more industrialization, people didn’t have that kind of experience. And there was this sense that people were really having children for the first time without having that kind of deep background in caregiving. And people like Benjamin Spock were kind of providing some of the same wisdom that, in the past, a grandmother or an aunt or someone else who was close to you would provide, or that you would have learned yourself.

Walter Issacson:

More than anything else, Spock’s legacy was empowering parents to adapt to social change. He tried to help parents reconstruct their child-raising village, emphasizing the importance of their own instincts and abilities. But increasingly parents are looking to technology to help close the gap as well.

Alison Gopnik:

I think the idea that technology is going to help us raise our children is pretty misguided. But on the other hand, what’s been true as long as we’ve been human is that part of raising children for human beings is raising them in an environment that is full of human technologies. I mean, after all, we’re the tool-using ape, and as long as we’ve been around, what we’ve done is have each generation deal with a slightly different world with slightly different technologies.

Walter Issacson:

So the question then becomes, how should I manage my child’s relationship with technology? But as a parent, you should also ask yourself, how should I be using the devices at my disposal? Technology should be a tool, not a crutch. And sometimes the most helpful tool is the one that lets you leverage the experience of other people.

Walter Issacson:

By the 1970s, another change was taking place. More and more women and mothers were entering the workforce and needed support raising their children. This meant the role of the father had to change too. The father was no longer just the breadwinner. He now needed to provide marital support and be an active participant in nurturing his children. But even though men were starting to bear more responsibility, they lacked guidance. They needed help adapting to their new role.

Walter Issacson:

Progress was slow and steady for a few decades. Then like many people looking for community, dads went online to find their village.

Mike Rothman:

I’m Mike Rothman, co-founder and CEO of Fatherly.

Walter Issacson:

After the 2008 financial crisis, Rothman noticed another shift in the world of modern fatherhood.

Mike Rothman:

At that point, we started to see a lot more dad blogs from newly laid off men who were grappling with this kind of new world order where they were now home with the kids and kind of dealing with what that looked like. And I think everything that I saw at the time felt like parody. Dad’s being goofy, cue slide whistle. And I thought that these representations of dads were all well and good, but it didn’t seem to reflect the needs of this new generation of fathers.

Walter Issacson:

Rothman outlined a new venture to serve this audience. He decided to start small with an email newsletter. In 2014, he cobbled together a subscriber base of 700 emails from a few fatherhood workshops and his own friends. Rothman believed the key to serving this new generation of dads is understanding that when men become fathers, they want to feel just as confident in their parenting abilities as they do with everything else in life. And this is how Fatherly found its voice.

Mike Rothman:

We set up a Tumblr and started publishing original articles. And some of these takes were, in fact, unique. And in terms of what you would find in the parenting universe. And our whole angle was find dramatically over-qualified experts to weigh in with very practical advice. So we found a Navy SEAL captain from SEAL Team 5 who gave tips on how to dominate hide and seek and how to be a master of concealment with all the things that you have in a living room. And it was at once genuinely useful, but also kind of hilarious. And so we started to develop a reputation for having a novel perspective on parenthood. And that was really how this prototype started to develop.

Walter Issacson:

Soon word spread like wildfire. 12 months later, Rothman had more than 50,000 subscribers. Rothman raised about $2 million in capital and officially launched Fatherly in April, 2015. Fatherly tackles lots of important topics parents inevitably encounter, including health, relationships, finances, and play. Today it has more than 700,000 daily email subscribers and a monthly audience of 20 million parents. Like other successful innovations in the parenting industry, Fatherly is meeting dads exactly where they need support, helping them construct a virtual village so they can raise happy, healthy, and confident children.

Mike Rothman:

You hear that parents need to put on their own oxygen mask first. And Fatherly is a kind of response to that, that helping men manage the emotional tumult of long-term relationships with a partner, with aging parents, new friend dynamics, and of course kids. And these are complex issues that require community, that require some expert advice, and that require ones like a kind of a reconciliation with one’s own upbringing.

Walter Issacson:

Parenting blogs and digital media companies, such as Fatherly, give parents access to experts all over the world and provide insights on kids of all ages. But perhaps the time when parents need the most help is right after they bring their firstborn home from the hospital.

Walter Issacson:

When babies are born and learn to feed, the first thing they need is sleep. Newborns need as much as 15 hours a day. And the first law of parenthood is when infants don’t sleep, parents don’t sleep either.

Walter Issacson:

Pediatricians report that sleep is a parent’s biggest concern.

Dr. Harvey Karp:

The solution to how to help babies cry less and sleep more and help parents be more skilled was right in front of our noses all the time.

Walter Issacson:

This is Dr. Harvey Karp. He’s a pediatrician and the co-founder of the startup, Happiest Baby. He’s devoted the majority of his career to helping parents address infant sleep issues.

Dr. Harvey Karp:

And in fact, we even almost understood it because over the last 20, 30 years, doctors would tell parents when your babies cry a lot, or when they’re not sleeping, there was a simple solution. Just drive them in the car all night long, and they would sleep an extra hour or two.

Walter Issacson:

Driving your baby around into the wee hours of the night might help her get a couple extra hours of sleep, but it’s certainly not going to help you get more rest.

Walter Issacson:

Lost sleep has a profound effect on caregivers, putting stress on families and amplifying postpartum depression. Postpartum depression can lead to lost work and wages and contributes to SIDS, or sudden infant death syndrome, which affects 3,600 babies in the US each year.

Walter Issacson:

But Karp recognized that there’s a reason babies sleep better in a moving car.

Dr. Harvey Karp:

What I came to realize was that babies are born with a reflex, literally with a built-in switch to calm their crying and to even fall asleep when you imitate the experiences that they have inside the womb, because inside the womb, it’s not quiet and still. It is a symphony of sensations. They’re constantly jiggled and rocked every time you breathe, even all night long when you’re sleeping.

Walter Issacson:

And that’s what a car ride does. To a certain extent, it imitates the experience of being in the womb. When Karp became a pediatrician, he developed a theory he calls the fourth trimester. This is the idea that in the first few months of life outside the womb, babies need a little help transitioning to new sleep routines.

Walter Issacson:

Then about a decade ago, he found himself at a crossroads. As he toured the country, giving lectures and presentations, he began to realize that his advice wasn’t making a big enough impact. So one evening, back in his hotel room after a lecture, he sketched his first prototype of what would eventually become the world’s first smart bassinet, a bed that responds to the babies and helps soothe them to sleep. In 2014, the SNOO Smart Sleeper was born.

Dr. Harvey Karp:

From the baby’s point of view, they feel like they’re in the womb. They’re held and rock. They’re cuddled in this special sleep sack. And then they’re gently rocked and shushed all night long. But when they fuss, the bed recognizes that, and it kind of jiggles them and shushes them louder as if you were having your baby in your arms, and you were bouncing them up and down. And if they continue crying, it goes to another level, and then yet another level to be able to settle them.

Walter Issacson:

Karp understands that his SNOO is there to assist parents. It’s not meant to abdicate responsibility or replace essential child/caregiver interactions. It’s there to help, and that’s key.

Dr. Harvey Karp:

The goal of SNOO is not at all to be a bed. We don’t even think of it as a baby bed. SNOO is a caregiver. SNOO is your older sister who came and said, go to sleep. I’m going to hold and rock this baby all night long. And if the baby gets upset, I’ll rock and shush more. And if I can’t calm the baby in a minute or two, I’ll get you. So SNOO is a robotic caregiver. The goal is to be an assistant. The goal is to help you do your human job better, just the way you might use a vacuum cleaner or a hairdryer or a food mixer. You use technology to help you accomplish the tasks that you feel are valuable in terms of caring for your child.

Walter Issacson:

Studying the impact of his new sleeper in more than 75 hospitals, Karp and his team found that nurses saved almost two hours per shift in time usually spent soothing babies to sleep. And at home babies sleep on their own an average of one to three hours per day longer than they did before.

Walter Issacson:

Studies show that babies and toddlers who did not get enough sleep are more likely to develop reading and language problems. Luckily, there’s a new technology helping parents assess and support child’s speech development.

Walter Issacson:

After sleep, the next significant milestone for children is learning to talk. Babies start to babble at around six to nine months, after which they’ll spend the next couple of years acquiring language from their parents and other caregivers.

Jill Gilkerson:

My name is Jill Gilkerson, and I am the chief officer of research and evaluation at LENA.

Walter Issacson:

LENA is a nonprofit organization dedicated to closing the opportunity gap for children who learn to talk at different rates. Falling behind in speech development can often lead to disadvantages in school and affect a child’s emotional and social wellbeing. And this is a source of major stress for parents and teachers alike

Jill Gilkerson:

Up until 15 years ago, when LENA was invented, the only way we could really know anything about a child’s language environment was through observers in the home, or from very short, one-hour audio recordings that require a lot of labor-intensive transcription. So it was clear we needed to know what was happening so we could instigate behavior change, but there was no way to do it unless you could figure out a way to do it automatically.

Walter Issacson:

LENA stands for a language environment analysis, and their technology can automatically measure how often children engage in language with adults. They designed a state-of-the-art recording device that fits inside the pocket of a child’s vest. It captures all relevant data in a child’s language and acoustic environment.

Walter Issacson:

Early on, the analysis focus mostly on counting words, but LENA’s researchers soon revealed that the real measure of language development is not only vocabulary, but what they call a conversational turn.

Jill Gilkerson:

So a conversational turn is basically a count of the number of times a parent and child engaged in back and forth. So if a parent says something, and a child responds, it could be a babble or a word, but if they respond within five seconds, that’s counted as one turn. And same if the child says something, and the parent responds within five seconds, that would be one back and forth, or one conversational turn.

Jill Gilkerson:

So we have found through many years of research that conversational turns are much more predictive of development than just looking at total number of adult words.

Walter Issacson:

At the end of a long day, the data from the child’s recording device is fed to LENA’s proprietary algorithm. It then compiles a list of detailed reports that parents and teachers can use to adapt and improve the child’s language environment. Sometimes it’s as simple as reminding parents to take a few more minutes each day to talk and respond to their child.

Walter Issacson:

Gilkerson says parents and caregivers see the value in LENA’s technology.

Jill Gilkerson:

They embrace the data. And when they saw it, and they made the changes, they really noticed improved relationships and improve language ability. So that totally underscores and reinforces the importance of their work and their efforts.

Walter Issacson:

Today LENA’s programs reach more than 10,000 children in centers across the US, including daycares schools and libraries. In the next three years, Gilkerson believes their reach will grow tenfold.

Walter Issacson:

By turning a cacophony of raw data into actionable advice, LENA’s programs not only ensure that children won’t be left behind, they also empower parents and teachers to help children thrive. But for any child to truly thrive, they need an education. And the first step in getting a quality education is learning how to read.

Walter Issacson:

As children learn to talk, they also learn to listen. When you’re a kid, there’s nothing quite like listening to someone tell you a story. Stories are an important way that kids learn about themselves and the world around them. And the wealth of knowledge children glean from stories expands when they learn to read.

Walter Issacson:

Today, however, the children’s book industry is being jostled by a worrisome technological intrusion, screen time.

Dana Porter:

So when we talk to parents all the time, anxiety is exactly the right word of what they’re feeling. Everybody’s got guilt that their children are either on their tablet, on the phone or watching TV.

Walter Issacson:

Dana Porter is co-founder and CMO of Inception XR. Inception XR is a creative studio striving to rewrite the story of screen time through their innovative app called Bookful.

Dana Porter:

We need to think about the change the children have gone through in the last era. If you and I played treasure hunts as kids, well, today they’re playing Pokemon Go in AR. So we see that augmented reality and interactivity are becoming such a core part of how children experience life. Well, if you want to make sure that reading stays relevant, it needs to talk in that same language.

Walter Issacson:

Bookful harnesses augmented reality to create a new kind of reading universe for children. But there’s a twist. Bookful isn’t just an entertaining smartphone app. It’s a digital learning tool. Porter and her team have infused AR and extended reality, or XR, with core principles of modern education. They encourage children not only to read, but to interact, create and express themselves.

Dana Porter:

So if you think about the evolution of reading, we’ve already, we started from print and then we went to digital. And the next evolution from that is actually to have more interactive and XR-enabled book. If we think of what, what are the real benefits of XR in education? You can explain complex concepts. You can promote independent learning. You can increase the engagement of a child with the content.

Walter Issacson:

Opening the Bookful app, a child experiences a vast learning library. They might start by reading a book like Dinosaur Days or the Tale of Peter Rabbit. Then they can use simple tools to make the images come to life in 3D.

Dana Porter:

Then the experience doesn’t stop there. You can then put that character in augmented reality in your own living room. You can dance. You can take a picture with it. You can take a video with it.

Walter Issacson:

A child using Bookful is not only reading, she is learning and using that knowledge to understand and influence her world. Over the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed just how important digital education has become in our lives. Screens aren’t going anywhere in the near future. So while it’s important for kids to participate in activities that don’t involve screens, parents also need to ensure that the time they do spend with screens is somewhat productive and educational.

Dana Porter:

So what we always tell parents is that we are not replacing that magical moment at bedtime when parents actually read to kids. We want actually to take a slice of their afternoon digital time, that slice of time where they’re either watching YouTube or playing shooting games, etc. and actually have them read books, develop a love of reading, play educational games. So Bookful is meant to take part of that digital entertainment time and not part of the traditional reading time.

Walter Issacson:

Whether it’s a baby formula or augmented reality kids’ books, parents have, and always will, use technology to help raise their children. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be critical of the technology we use, especially when it comes to parenting. Parenting and child development innovators have helped us adapt to our shrinking village, but technology will never be the answer to the question, how do I raise my child well?

Walter Issacson:

If you think about the most important characteristics of a community, you’ll probably make a list of things like support, encouragement, wisdom, respect, and love. These are also the things parents need most as they figure out how to raise their kids. Most of us will never live in a traditional village, but as our world changes, it’s important to remember that the village can change too. We just need a little help rebuilding it, and as Dr. Spock said, a bit of common sense too.

Walter Issacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson, and you’ve been listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Walter Issacson:

If you’d like to learn more about any of the guests on today’s show, visit delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

In days past, parents weren’t the only ones responsible for raising their children, with neighbors, family and friends all chipping in to help. As parenting has become more focused on families, technology has stepped in to assist. Discover some of the most innovative ways people are solving child-rearing challenges on a new Trailblazers.

In days past, parents weren’t the only ones responsible for raising their children, with neighbors, family and friends all chipping in to help. As parenting has become more focused on families, technology has stepped in to assist. Discover some of the most innovative ways people are solving child-rearing challenges on a new Trailblazers. Jennifer Traig

is the author of “Act Natural: A Cultural History of Misadventures in Parenting”

Jennifer Traig

is the author of “Act Natural: A Cultural History of Misadventures in Parenting”

Alison Gopnik

is a professor of psychology at the University of California at Berkeley and a world leader in cognitive science, particularly the study of learning and development. She is the author of “The Scientist in the Crib” “The Philosophical Baby” and “The Gardener and the Carpenter.”

Alison Gopnik

is a professor of psychology at the University of California at Berkeley and a world leader in cognitive science, particularly the study of learning and development. She is the author of “The Scientist in the Crib” “The Philosophical Baby” and “The Gardener and the Carpenter.”

Harvey Karp

is a world-renowned pediatrician and child development expert. He is the creator of the SNOO Smart Sleeper, a new class of responsive infant bed that adds 1-2 hours to a baby’s sleep and reduces the risk of infant sleep death by preventing dangerous rolling.

Harvey Karp

is a world-renowned pediatrician and child development expert. He is the creator of the SNOO Smart Sleeper, a new class of responsive infant bed that adds 1-2 hours to a baby’s sleep and reduces the risk of infant sleep death by preventing dangerous rolling.

Mike Rothman

is the co-founder of Fatherly, the leading digital lifestyle brand for today's parents. Through a combination of expert advice, live experiences and consumer products, Fatherly empowers dads and moms to raise great kids and lead more fulfilling adult lives.

Mike Rothman

is the co-founder of Fatherly, the leading digital lifestyle brand for today's parents. Through a combination of expert advice, live experiences and consumer products, Fatherly empowers dads and moms to raise great kids and lead more fulfilling adult lives.

Jill Gilkerson

is the Chief Research and Evaluation Officer at LENA, a national nonprofit on a mission to transform children’s futures through early talk technology and data-driven programs.

Jill Gilkerson

is the Chief Research and Evaluation Officer at LENA, a national nonprofit on a mission to transform children’s futures through early talk technology and data-driven programs.

Dana Porter

is the the co-founder and CMO of Inception XR, a leading mixed reality content and technology provider. Inception XR is a creative studio striving to rewrite the story of childhood screen time through their innovative app, called Bookful.

Dana Porter

is the the co-founder and CMO of Inception XR, a leading mixed reality content and technology provider. Inception XR is a creative studio striving to rewrite the story of childhood screen time through their innovative app, called Bookful.