Walter Isaacson:

It’s July 17, 1937, and a young woman named Mary Miller is in a bind. After a series of real estate deals gone wrong, Mary is at serious risk of losing her last property, her only defense against complete financial ruin. Things are looking pretty bleak for Mary. She’s out of money and out of time, so she decides to take a chance and rolls the dice. It’s snake eyes. Mary is forced to sell her last piece of property, but the meager sum she gets in return isn’t even enough to rent a place on humble old Baltic Avenue. Mary is bankrupt. Game over.

Shane:

Yeah! Woo!

Walter Isaacson:

Her brother Shane jumps up from the table with a loud cheer.

Shane:

I can’t believe I won.

Walter Isaacson:

Snapping 12-year-old Mary out of her fantasy. Shane, two years her senior, is ecstatic because this is the first time he’s ever beat his sister at their favorite board game, Monopoly. Since its release in 1935, Monopoly has been translated into 35 languages and is played in more than 103 countries around the globe. It’s arguably the world’s most famous board game, but this iconic pastime we now associate with cutthroat capitalism had a very different message when it was first conceived.

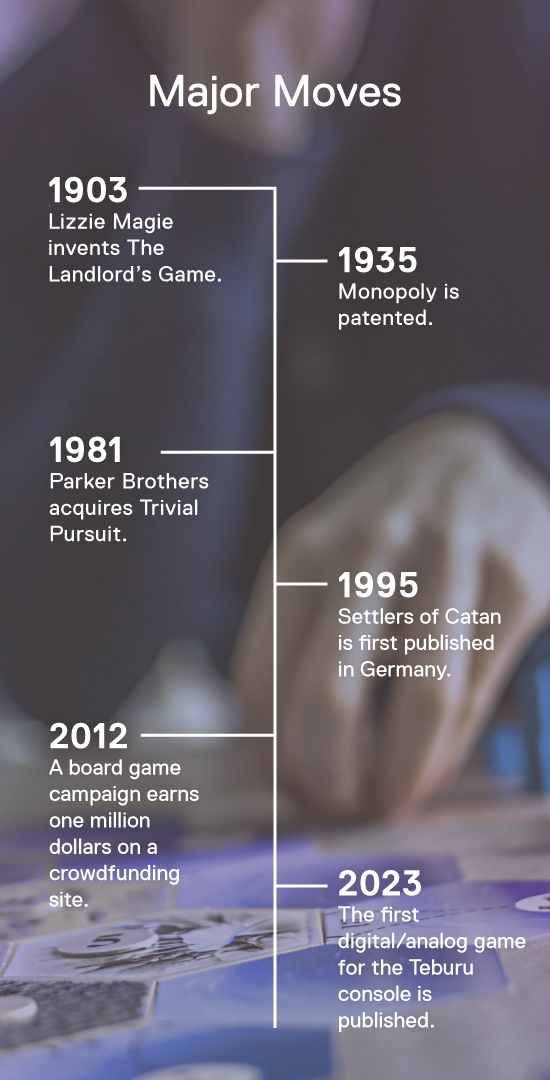

Created in 1903 by a politically conscious woman named Lizzie McGee, the original name for Monopoly was The Landlord’s Game. McGee hoped that the game would illustrate the perils of capitalism and promote a form of taxation that would curb the disproportionate power that landlords had over renters in the early 20th century. Soon after McGee self-published her new board game, economics professors were using it as a teaching tool in their classrooms. But before long, students decided it would be more fun if they changed the goal of the game to monopolizing properties and bankrupting other players.

Eventually, the game spread beyond universities and adopted the informal name Monopoly. As it was passed from friend to friend through communities and towns, rules were tweeted and players customized their own handmade boards. Eventually, the game reached an unemployed salesman named Charles Darrow, who quickly realized the game just might be his golden ticket. So he redesigned the board, adding colored bands to differentiate properties, a free parking space, and the policeman who tells players to go to jail. In 1935, Darrow sold the game to the toy and game manufacturer Parker Brothers.

In just six months, the company sold a quarter million copies. By 1936, that number had reached 1.8 million. It wasn’t until 1974, 26 years after her death, that someone discovered the patent for The Landlord’s Game and Lizzie McGee finally received credit for creating Monopoly.

Sadly, McGee did not reap the rewards of her hit game during her lifetime. But it’s also true that without the contribution of each person who played and adopted The Landlord’s Game, there would be no Monopoly as we know it. Today, 88 years after Parker Brothers first release Monopoly, we’re in the midst of a board game renaissance. Crowdfunding and digital game platforms have helped reinvigorate the industry and given enthusiasts a hand in developing the games they love.

In fact, it’s projected that the global board game market will more than double in the next six years, reaching a value of more than $30 billion by 2028, and that’s a fun prospect for both game developers and their fans. I’m Walter Isaacson and you’re listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Speaker 3:

Today, we’re going to play an exciting new game.

Speaker 4:

The game for people who love to laugh, buy the Bankers of Monopoly.

Speaker 5:

Complete with stunt match, cards, horns, clickers, tricks, spinner and monkey timer.

Speaker 4:

Funny Bones is a Parker game. Get it wherever toys are sold.

Speaker 5:

Where the fun comes from.

Walter Isaacson:

Monopoly helped usher in the golden age of board games in the mid 20th century, but business tycoon George Parker, the founder of Parker Brothers game company, started transforming the industry decades before his company’s flagship game hit the shelves. In the 19th century, most board games were designed to emphasize wholesome values. In fact, one of the earliest games published in the US during this time was called The Mansion of Happiness, a board game intended to inspire Christian morals in children, but Parker had a different board game philosophy.

So in 1883 at the age of 16, he introduced his first game and it was a little less, well, moral. It was called Banking, and the objective of the game was to get as rich as possible.

Philip Orbanes:

Now, why did Parker create this game? I think that’s just as important as the game he created.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Philip Orbanes. He’s the former vice president of research and development at Parker Brothers and the author of Monopoly: The World’s Most Famous Game and How it Got That Way.

Philip Orbanes:

It’s because up until that point, all of the games that his gaming club of friends had played were either serious like chess or Checkers, strategy games, or they all taught moral lessons like the Mansion of Happiness, which represented your pursuit of getting into heaven. And the club felt that games should be fun.

Walter Isaacson:

Parker’s Banking game became so popular amongst his friends that his brother encouraged him to publish it. So Parker self-published 500 copies selling every single one. Then in 1884, buoyed by this early success, Parker decided to launch his own board game company. After convincing his two older brothers to join his growing business, he changed the name to Parker Brothers. But as Parker Brothers continued to grow, their success to the attention of a competitor, Milton Bradley. Bradley, who had incorporated two decades earlier and made, as he called them, educational toys, suddenly found himself playing catch up.

Philip Orbanes:

So the rivalry between Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers began to heat up throughout the first half of the 20th century. In the roaring ’20s, there were just two major game companies of consequence, Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers, and they basically set the tone of the race for the next several decades.

Walter Isaacson:

The Great Depression of the 1930s brought financial hardship to both companies. Then in 1935 in a moment riddled with irony, Monopoly exploded onto the scene. Suddenly swapping fake cash and making imaginary real estate deals was a favorite pastime for people in financial despair. It’s a moment that set the stage for the golden age of board games in the 1940s, which brought us some of the industry’s most enduring titles.

Philip Orbanes:

One of the distinguishing things about the origin of our most beloved games is that they sprang forth in the minds of people who were not game inventors. A great case in point is Clue. Clue was created during World War II by a former lounge pianist who was working in a factory making parts for tanks in Birmingham. And to pass the time, especially during the Blitz, he and his wife created a murder mystery game. And another game that comes to mind is the great conquer the world game, Risk. This began in the mine of a movie producer in France, and actually the impetus for him creating this was the Cold War.

And those two games actually revolutionized what board games could be. Any number of detective games have come out since, and Risk actually launched an entire industry of military battle simulation games.

Walter Isaacson:

Clue and Risk were both manufactured by Parker Brothers. Milton Bradley shot back with games such as Battleship and Conspiracy, but the biggest revolution in board games was still to come, and it had nothing to do with war, murder, morality, or getting rich. One day in 1979, friends Scott Abbott and Chris Haney were playing a game of Scrabble when they realized they were missing a few letter tiles. So unable to play one of their favorite games, they decided to invent their own. In 1981, Parker Brothers acquired their game and changed the board game industry forever.

Philip Orbanes:

Trivial Pursuit opened up an entirely new category of games called adult social games. Yes, there had been social games and trivia games prior to Trivial Pursuit, but nothing like Trivial Pursuit itself. Within the first 12 to 15 months, they sold an astounding 20 million and Monopoly’s best year, by the way, was like three and a half million. And so Trivial Pursuit probably doubled the size of the board game business with the new ground that it broke.

Walter Isaacson:

30 million games were produced between 1983 and 1985. And just as Trivial Pursuit was taking over the world one fact at a time, another seismic change rocked the board game industry. In 1984, toy and entertainment giant, Hasbro bought Milton Bradley, and when Parker Brothers was swallowed up by Hasbro in 1991, the old arch rivals were merged into a single division. But even this industry juggernaut wasn’t strong enough to neutralize the threat of a new entertainment product rapidly gaining and popularity, video games.

The 1990s was an era that spelled the end from many smaller board game manufacturers. But after years of poor sales and waning popularity, many video game enthusiasts started to get nostalgic. In response to the explosive proliferation of video game culture, people began to find a renewed sense of interest for what came to be known as analog gaming or in layman’s terms, playing a game across a table with other people. And this nostalgia was just in time for a new breed of strategy-based adventure games that encouraged player interaction within immersive campaigns and scenarios.

A big departure from the typical turn taking format of many popular board games from the 20th century. The game that led this charge began its journey around the kitchen table in Germany.

Guido Teuber:

My dad would bring game designs and we would play the games, and then we could even review them and sometimes we would tell him that they weren’t so great and we were disappointed, and then he brought back a better versions.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Guido Teuber, the son of Settlers of Catan creator Klaus Teuber. Eventually, Guido and his siblings gave their father’s game the thumbs up.

Guido Teuber:

Imagine you are a settler, you have been driven out of your homeland, and you are with a small tribe in search of a better world. And after a long journey on the ocean, you discover this island and all of a sudden there is a world of opportunities.

Walter Isaacson:

Settlers of Catan or Catan for short was born out of Klaus Teuber’s love of storytelling and his fascination with ancient Viking traders. It was in line with other Euro game designers from this period who favored the medieval and early modern era as source materials instead of 20th century conflicts. And for Teuber the fun immersive narrative he crafted about a Klan of Vikings settling an unexplored island allowed him to marry the social appeal of board games with the expansive interactive world of video games. It was a recipe that lured millions of people looking for human connection back to the table.

Guido Teuber:

We were surprised that it became such a breakout hit at the very beginning because we had underestimated how much there was a willingness for more complex games in the mainstream. And in 1995, there was a tipping point where people were hungry for more content, for more than just rolling the dice and moving pieces on a board. And Catan came at the right time and the right place in Germany.

Walter Isaacson:

First released in Germany, and then across Europe, Settlers of Catan was an instant hit. And while it took Americans a bit longer to put down their video game controllers, Catan eventually caught on in the US as well. When it did, the enthusiasm was very, well, American.

Guido Teuber:

From my German perspective, when Americans get into something they really get into it. People are so excited that they dress up in Catan themed costumes at Halloween, and that’s just one of the indicators. So the amount of enthusiasm that people have now for board games and including the Catan brand is unparalleled. I have not seen that in any other country.

Walter Isaacson:

Catan almost single-handedly launched a whole new era in the industry. It inspired a new wave of game designers trying to bring more complex adventure-based strategy games into the commercial gaming space, but it’s a highly competitive market. And pitching game concepts to gargantuan manufacturers like Hasbro has never been an easy road.

Jonathan Ritter-Roderick:

Our first game, it’s called Dragoon. Theme of the game is that you’re a dragon and you’re trying to conquer a countryside basically and get as much gold as you can.

Walter Isaacson:

This is the board game designer, Jonathan Ritter-Roderick.

Jonathan Ritter-Roderick:

And it comes with really high quality pieces, which is the way we kind of set ourselves apart. A lot of people early on and understandably told us that we were kind of crazy for doing this. They were like, it has metal pieces that are finished in real gold and real silver and has a cloth board. It’s too much money. And we kind of just said, screw it, we’re going to do it anyway.

Walter Isaacson:

Ritter-Roderick believed there was an audience for Dragoon, but first he had to find a manufacturer to produce the game.

Jonathan Ritter-Roderick:

Could we get this published? Would a company that’s existing be willing to take this on and make it themselves? And no one wanted to do it with the metal, and we all said we do. So let’s find another way.

Walter Isaacson:

That way was Kickstarter. Launched in 2009, Kickstarter is a crowdfunding platform with a mission to help artists bring their projects to life.

Jonathan Ritter-Roderick:

So the way Kickstarter works is your campaign. It has a set goal, like a monetary goal that you want to hit. If you hit that monetary goal, you are then in “funded” and you’ll receive the funds. If you don’t reach that goal, you won’t receive the funds. So it’s an all or nothing platform.

Walter Isaacson:

Kickstarter cuts out the middleman. Instead of trying to convince traditional industry gatekeepers to fund an idea, designers seeking startup capital can appeal directly to their audience. And in exchange for backing an idea, funders get early access to the product and other perks. Hobbyists valuing this early access to board games flocked to the new site. After a few years of operation, Kickstarter quickly realized that board game campaigns were going to be a big part of their success. In May 2012, two board games earned roughly 800,000 and $1 million respectively.

These numbers were unprecedented and they got the attention of other game designers, including Jonathan Ritter-Rodrick.

Jonathan Ritter-Roderick:

We thought we were like maybe going to raise like five or $10,000. We ended up raising 88 and it was a amazing, and it kind of brought me into this industry and made me realize that this was something I both loved doing and could possibly do for the rest of my life.

Walter Isaacson:

Today, Ritter-Rodrick is a director of games at Kickstarter. One of his favorite aspects of Kickstarter is that every campaign on the platform has a dedicated chat room, so fans can offer creators suggestions on how to improve their game.

Jonathan Ritter-Roderick:

It’s pretty amazing that you have the ability to influence something that is like this wild character that you never thought was going to be in a game, but you can suggest it. And if the creator is into it, then all of a sudden it’s in the game.

Walter Isaacson:

This kind of crowdsourced feedback is reminiscent of the hive mind that transformed Lizzie McGee’s The Landlord’s Game into the version of Monopoly we know today. And other platforms are taking player input and the fan creator relationship even further. The online gaming site Tabletop Simulator allows fans to play digital versions of their favorite games, create add-ons for those games, and even build completely new games. In 2020, fans of the hit board game Gloom Haven made use of Tabletop Simulator in a very interesting way.

After it was announced that the highly anticipated sequel to Gloom Haven would be delayed due to the pandemic, Gloom Haven’s creators released the game’s assets to fans so they could create an online game set in the same universe as Gloom Haven to be played while they waited for the sequel. The result was a new game dubbed Crimson Scales. It had new characters, 60 additional scenarios and fresh artwork. Released on Tabletop Simulator, Crimson Scales generated so much excitement that the Gloom Haven creators allowed a print of the made expansion to be downloaded and sold as a physical board game.

This kind of fan engagement created so much buzz for the delayed Gloom Haven sequel that its Kickstarter campaign eventually generated $13 million in pledges. Kickstarter has ushered in a board game renaissance. It’s allowed thousands of designers to find funding, and it’s helped fans move games they like from the idea stage into the living rooms. One creator who’s benefited from this crowdfunding revolution is Marcin Swierkot.

Marcin Swierkot:

So our game Tainted Grail was the biggest 2019 campaign of Kickstarter. We got our $6 million.

Walter Isaacson:

Swierkot is the founder and CEO of the game design firm Awaken Realms. He wanted to take crowdfunding one step further, so he founded his own crowdfunding site game, Gamefound.

Marcin Swierkot:

Like the natural next step for the crowdfund would be what if instead of just offering a platform where you could create a campaign, what if this platform could also take up from you all the logistics work, all the project management work? Gamefound can take all the kind of not exciting work from you, not creative work, a lot of standard kind of e-commerce things that, but also help you as a creator to develop this project to make it happen.

Walter Isaacson:

Gamefound removes some of the complexities of running a business for its users. But complexity is actually something that fans love about Swierkot’s board games. Awaken Realms is known for its intricate and immersive story driven games such as Nemesis, a sci-fi survival horror set on a malfunctioning spaceship. But Nemesis and other titles like it have begun to reach the outer edges of what a traditional board game can achieve. One challenge in this elite space is how to keep expanding the game’s narrative without making the game too overwhelming to learn.

Marcin Swierkot:

Just imagine that before playing our board game, you’d have to read 60 page manual, but not everyone has time and kind of amount of effort to kind of dedicate towards that. So kind of like digital game is a very natural next step.

Walter Isaacson:

For Swierkot, the answer to this problem can be found in adapting his board games into video games. When people play a board game, they need to learn the rules up front. But because video games guide your players, you navigate a virtual world, you can learn the rules as you go. But Swierkot wants to go beyond the digital options that are offered in the simulator space.

Marcin Swierkot:

So the digital games that we’re making, we put a different approach because there is digital adaptation of board games. Our kind of business opinion, personal opinion is that every medium has its own use and its own pros and cons. We didn’t thought that replicating board games one-to-one into digital space will be actually a good idea. Our strategy is just to create different types of games, but set in the same universes that we have created on the board games. So it is like 100% digital game, totally different product.

It is a normal video game, but it is set in the same world, leaning on the stories that we told in the board game and using the same art direction.

Walter Isaacson:

It’s an approach that’s working. In September 2021. Swierkot’s first board game inspired video game Tainted Grail Conquest was released on Xbox. Board games are now inspiring video games, an ironic turn of events when you consider that 25 years ago, video games almost put board game designers out of business. Now it’s a profitable new revenue stream. But while Swierkot has brought board games into the digital realm, other designers are bringing the digital realm to board games.

Davide Garofalo:

So my name is Davide Garofalo and the company I founded is Xplored. And the product that we’re talking about is Teburu.

Walter Isaacson:

Teburu is a groundbreaking innovation. It’s a board game console, similar to a video game console like Xbox or PlayStation that connects to physical board games, creating a hybrid digital analog game experience tab. Teburu’s technology is hidden inside of a foldable game board that’s about the size of a Monopoly board. It’s embedded with sensors that track player movements to calculate the probability of future game events. This automated number crunching allows game enemies to adjust their behavior based on player movements.

Davide Garofalo:

And so as soon as you move, you hear the sound of your footstep, you hear the music that changes because maybe an ambush is coming. And then if you have enemies in the game, instead of managing yourself the enemies based on what you read on a source book in a manual, it’s the system that use an artificial intelligence to move them so that the enemies and the game and the villain can take decisions that are weighted because also they know where you are, where is the most dangerous character for them.

So they can tune around, they can hide, they can take weighted decisions like in a video game, but all the interaction is physical.

Walter Isaacson:

To realize this vision, Garofalo and his team needed to raise money. So like many designers before him, he turned to Kickstarter. The $300,000 he raised was enough to start prototyping the first to Teburu compatible game.

Davide Garofalo:

It is called The Bad Karmas and the Curse of the Zodiac. And I have to tell you that the moment when we moved the first miniature on a board and we heard the sound of the footstep and we heard the sound of the door opening and the ambush of the enemy popping out from the room, it was exactly at all our mind were imagining six months before and then it was happening and we said, yes, we did it. We have something cool in our hands.

Walter Isaacson:

But the real test for Garofalo is when he took Teburu to Gen Con, one of the biggest gaming conventions in the world and asked for feedback on his new system.

Davide Garofalo:

The most skeptical people, journalists, players, operators of from the industry who sat down, even if at the beginning they were very skeptical, at the end, they were the ones selling the game to other people and they were bringing other people to the table saying, you cannot understand. You have to try. Sit down and try.

Walter Isaacson:

And much like a video game, these converted skeptics learned as they played.

Davide Garofalo:

So in the first 10 minutes, they learn it without stopping to read the rule book, without making the calculation, without managing the tokens on the board, all that is managed by the system. So that’s what the video game technology cannot.

Walter Isaacson:

Garofalo has big dreams for Teburu. Eventually, he wants the system to be compatible with existing narrative driven games such as Nemesis. But an even bigger goal is to help independent creators and fans develop program and customized games for the platform. In fact, enhanced engagement is a deal he made with Teburu’s funders and it’s a smart deal. Because like the many hands that help transform Monopoly into the game we know today, board games are best when fans have a say in how they’re made and the stories they tell.

And now with digital tools opening the door for even more sophisticated and immediate community feedback, the possibilities seem endless. It would appear the longstanding rivalry between video games and board games is cooling. The two mediums continue to inform one another and make each other better. And devices like Teburu are emerging digital tech with analog gaming to create a completely new fan experience. But for Philip Orbanes, our love of board games goes beyond the game itself. It’s about what happens off the board that matters most.

Philip Orbanes:

The reason why people get into board games and really enjoy the experience is because they instantly cause you to let down your guard to be a kid again, perhaps, and to share parts of yourself that otherwise you keep under lock and key. So it’s that opening of your inner self and the ability for you to learn much more about the players that you’re with that just doesn’t occur unless you’re playing a board game.

Walter Isaacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson and you’ve been listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies who believe there’s an innovator in all of us. If you want to learn more about the guests in today’s episode, please visit dellftechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

In the mid twentieth century, the golden age ofboard games, two companies dominated themarket. Now, niche game designers can reachtheir audiences directly on crowdsourcing sitesand through conventions. Fans can investmoney in compelling games and give feedbackand suggestions to the designers. After thevideo game dominance of the 90s cooled, someboard games have become world-widephenomenon and others have inspired thecreation of their own video games. There arenow so many ways to game and thecombination of innovative technology andclassic tabletop fun is pushing the limits ofwhat’s possible. Hear more about this winningformula on this episode of Trailblazers.

In the mid twentieth century, the golden age ofboard games, two companies dominated themarket. Now, niche game designers can reachtheir audiences directly on crowdsourcing sitesand through conventions. Fans can investmoney in compelling games and give feedbackand suggestions to the designers. After thevideo game dominance of the 90s cooled, someboard games have become world-widephenomenon and others have inspired thecreation of their own video games. There arenow so many ways to game and thecombination of innovative technology andclassic tabletop fun is pushing the limits ofwhat’s possible. Hear more about this winningformula on this episode of Trailblazers. Philip Orbanes

is the former Vice President of R&D at Parker Brothers and the author of "Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game—And How it Got that Way".

Philip Orbanes

is the former Vice President of R&D at Parker Brothers and the author of "Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game—And How it Got that Way".

Guido Teuber

is the son of Settlers of Catan inventor, Klaus Teuber and the managing directors of CATAN GmbH. A completely unknown “German game” from 20 years ago became a modern classic game in North America.

Guido Teuber

is the son of Settlers of Catan inventor, Klaus Teuber and the managing directors of CATAN GmbH. A completely unknown “German game” from 20 years ago became a modern classic game in North America.

Jonathan Ritter-Roderick

is the Director of Games at Kickstarter, where he has helped games creators raise over $850M since 2020. His start in games began when he and his friends made the board game Dragoon, which successfully launched on Kickstarter in 2015.

Jonathan Ritter-Roderick

is the Director of Games at Kickstarter, where he has helped games creators raise over $850M since 2020. His start in games began when he and his friends made the board game Dragoon, which successfully launched on Kickstarter in 2015.

Marcin Świerkot

is a game designer, the founder and CEO of the board game design company, Awaken Realms and Gamefound, the crowdfunding platform dedicated for tabletop games.

Marcin Świerkot

is a game designer, the founder and CEO of the board game design company, Awaken Realms and Gamefound, the crowdfunding platform dedicated for tabletop games.

Davide Garofalo

is a multi-disciplinary manager, gaming designer and founder and CEO of Xplored: a game innovation studio based in Italy, working in full development from concept to release, for hardware & software IPs. Xplored is the owner and creator of the multi-patent Teburu system, successfully crowdfunded in 2022, and its digitally enhanced board games.

Davide Garofalo

is a multi-disciplinary manager, gaming designer and founder and CEO of Xplored: a game innovation studio based in Italy, working in full development from concept to release, for hardware & software IPs. Xplored is the owner and creator of the multi-patent Teburu system, successfully crowdfunded in 2022, and its digitally enhanced board games.