The map is not just an information resource, however: It’s a storytelling device that brings life to complicated sets of data and insights in a format that anyone can read. “If we’re going to achieve these circular economy goals, and have more resource recovery, we’re going to have to have behavior change,” says Groves. The hope is that by seeing how waste is handled, businesses and individuals will make more sustainable buying decisions and manage their garbage better.

“Once you start to get a picture, once you know where material is, you’ve effectively got a resource map,” says Groves, alluding to the potential in waste mapping technology to ultimately act as a guide for those looking for recycled raw materials.

If we’re going to achieve these circular economy goals, and have more resource recovery, we’re going to have to have behavior change.

—Michael Groves, founder and CEO, Topolytics

A changing relationship with waste

When it comes to tackling the world’s waste, the focus is on large organizations and governments—those with the largest volumes of waste and the power to change the systems used for disposing of it. Indeed, over half of the world’s plastic waste is produced by only 20 firms. But citizens and individual consumers also have an opportunity when making decisions about buying and disposing of material.

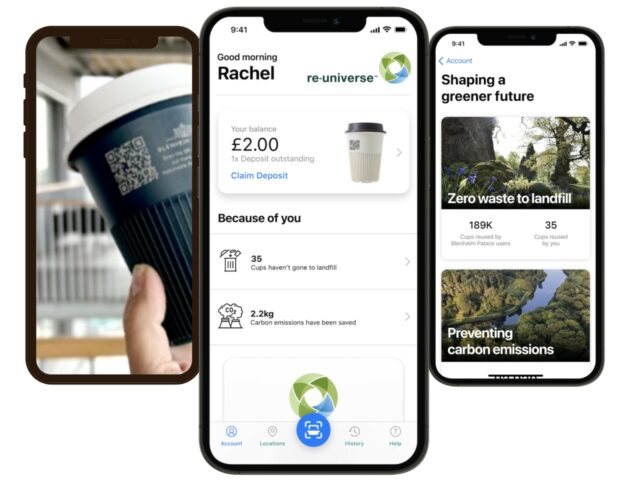

“When you go and buy something, and it’s in some packaging—that packaging, you’re effectively taking on responsibility for it,” says Tony McGurk, co-founder and chairman of re-universe, a reuse and recycling platform that allows consumers to be rewarded financially for recycling their waste. “We can give everything an identity, and once you give things an identity, you have traceability.”

Deposit laws are government programs whereby citizens pay a deposit when they buy a product, which they then get back when they return the packaging to the point of sale to be recycled. The platform created by re-universe digitalizes the process of verifying the return—meaning that people can use the app to scan (and submit for tracking) their recyclable waste and then place it in their recycling bins. It gives visibility for those programs to feed directly into existing bin collection systems and reduces the ask put on citizens. “The only reason we can make it easy for people is because technology allows us to do that,” says McGurk.

By mapping waste systems, people can increase their understanding of the materials they accrue and see their cast-offs not as garbage but as stuff that still has life. Technology is making waste—and its value—visible like never before.

Lead image of a woman recycling courtesy of Great Hoffman/Pexels.

If waste isn’t wasted, then surely it ceases to be waste? It sounds like a logic puzzle, but it’s the core idea behind recycling; one person’s trash is another person’s treasure. And like any good treasure, you need a map to find it.

Enter the world of waste mapping. Those at the forefront of this industry seek to unlock the value of garbage and—in doing so—protect the planet.

While paper recycling has existed for over 1,000 years, there’s still much to be done when it comes non-paper goods. Only 9% of the world’s plastic waste has been recycled, for example. The problem remains multifaceted: waste is recycled in different ways in different places; it’s part of a fragmented chain of responsibility; and it’s not effectively tracked. This makes it difficult to source reusable materials for new products and complicates tracking non-recyclable waste to ensure it is disposed of safely.

By working to eliminate those obstacles, waste mapping is bringing us one step closer to a circular economy.

Wrestling the complex with maps

“We’re looking at COVID-19 shocks, and companies are thinking: Wow! If we can’t get hold of that material, we need to basically be using the material that we have more efficiently.’ So that is driving a much greater focus on resource efficiency,” says Michael Groves, founder and CEO of waste data and analytics startup Topolytics. “The geography of waste is one part of what we do.”

The company’s platform, WasteMap, maps and analyzes waste, its processing and its multiple players in the global system. “You’ve got this real patchwork and complexity around the way material is defined and measured and moved, which makes the data highly variable. We use data science to fill the gaps and start to see patterns.”

WasteMap pulls data from spreadsheets of various waste processing organizations, sensor data from bins all over the globe, onboard tracking devices of waste management vehicles and any other kind of third-party data platforms that their clients might want to draw on. The software compiles, combines, analyzes and makes predictions using machine learning algorithms to unearth what’s going on in particular waste management systems. Then, it displays relevant information in maps, graphs, charts, summaries—whatever form is most useful for whoever is using the platform.

For example, Topolytics built a digital reporting system that gathers and centralizes all waste data across the U.K for the U.K. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. The system provides easy-to-use dashboards for local policymakers and those enforcing regulations. WasteMap allows for the waste to be more visible, easily verified, and, ultimately, valuable for those who want to reuse it.

Finding diamonds in the rough

Organizations can also track their own waste with the software, finding patterns in their waste habits and ultimately making better decisions about how to manage their garbage. For instance, a factory could visualize the lifecycle of its byproducts—how much is created, where it is moved, how much is used by downstream consumers and how much ends up in a landfill. Having insight into their environmental impact and the value of their waste could inform byproduct processing to be more environmentally friendly and commercially valuable. Maybe they choose to sell the byproduct directly, for example.