Walter Isaacson:

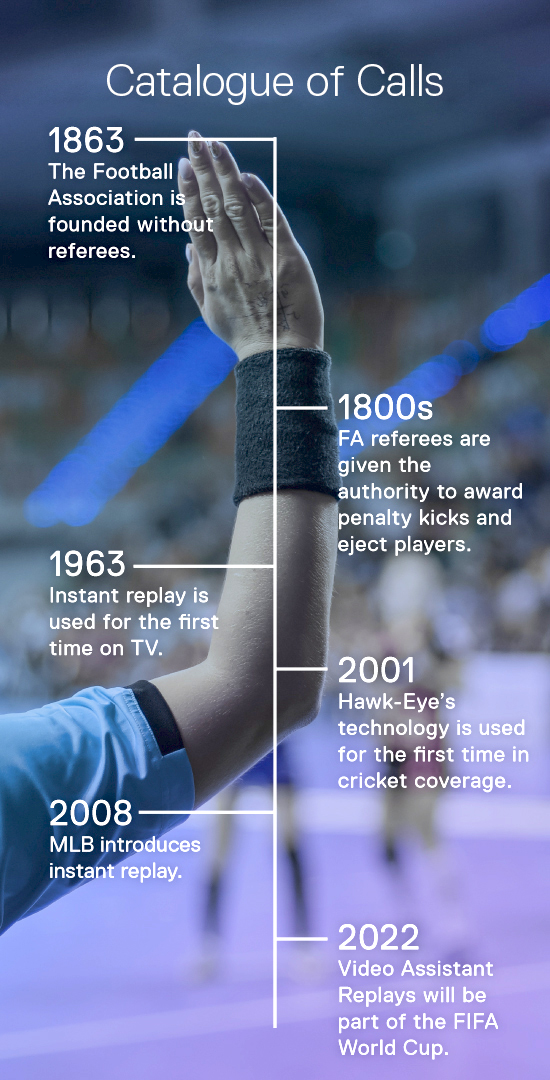

There have been many memorable moments in the long history of the Army-Navy football rivalry, but for sheer heart-stopping excitement, the epic battle that unfolded during their 64th meeting in 1963 ranks right near the top. Navy is a heavy favorite coming into the game so with 10 minutes left on the clock, no one is surprised that they’re up 21-7 over Army. They seem to be cruising to victory, but then the tables begin to turn and it’s Army quarterback Rollie Stichweh who provides the heroics. With the clock ticking down, Stichweh runs for a touchdown. Then a two-point conversion makes the score 21-15. Army only needs one more touchdown to tie the game. Fans watching at home see Stichweh score his fourth quarter touchdown and then a moment later, they see Stichweh score again, but Army had not tied the game. Television viewers had just witnessed instant replay being used for the very first time during a live sporting event. This is so unusual that the play-by-play announcer feels the need to tell viewers-

Speaker 2:

This is not live, ladies and gentlemen. Army did not score again.

Walter Isaacson:

Unfortunately, Army ran out of time before they could complete the comeback, but as exciting as the game was, the most significant thing that happened that day didn’t occur on the field. The real hero of the game was the television producer at CBS who introduced the world to instant replay, Tony Verna. Videotape was not new in 1963, but it was unwieldy, slow, and inaccurate. It was hard to locate the exact spot on the tape where the replay should begin, but Verna had an idea how to solve the problem. Verna started by recording beeps on an unused audio track while he recorded the live action. Then he used those beeps to quickly and accurately find the precise spot where the replay should begin. Verna spent most of the Army-Navy game trying to perfect the technique and by the fourth quarter, he had finally figured it out. Watching sports on television would never be the same.

Walter Isaacson:

But it wasn’t just TV viewers whose lives were changed that day. It took several decades to perfect the technology, but today, video replay has become an essential part of officiating in every major professional sport. Decisions that once relied solely on the judgment of one or two highly skilled, but very human, officials on the field, can now be made in sophisticated high-tech replay centers often hundreds of miles away. Imperfection is one of the things that has always made watching sports so compelling. Even the best players can fail when everything is on the line and that used to be true of officials as well, but today with the ever-increasing use of tech to help officiate sports, that is quickly becoming a thing of the past. I’m Walter Isaacson and you’re listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Speaker 3:

And the crowd likes it.

Speaker 4:

I don’t know. Let his emotions get in the way of making a proper call.

Speaker 5:

It’s called foul by the first base umpire.

Speaker 6:

Replay experts being part of my football game is not something I ever thought would happen.

Speaker 7:

It’s actually a tough job.

Speaker 8:

The first rule of good sportsmanship, play fair.

Walter Isaacson:

We’ve become so accustomed to referees or umpires deciding what’s legal and what’s not that it’s hard to imagine a time when that wasn’t the case, but in the 19th century before the formation of professional leagues, referees were almost an afterthought at sporting events in the US and in England. In fact, when England’s first soccer league was formed in 1863, there was no mention of referees or umpires in its rule book. In those early years, the game was very popular among students at elite private schools and the prevailing wisdom was that players did not need referees to tell them to obey the rules.

Tom Webb:

We’re talking about educated people, members of society at that time in England that were seen as higher society.

Walter Isaacson:

That’s Tom Webb. Webb is a lecturer at the University of Portsmouth and the author of several books about refereeing.

Tom Webb:

So they’d been brought up within families of wealth, of education, and so it was seen that they could adjudicate themselves at that time.

Walter Isaacson:

During a match, captains would each choose a representative that they called an umpire. If there was a dispute over the rules, the two umpires would confer and reach an agreement. It was a gentleman’s game played by gentlemen, but there would be times when the umpires couldn’t agree. That’s where referees entered the picture.

Tom Webb:

The referees were people that were chosen by the umpires to adjudicate on any points or decisions that the umpires couldn’t agree. So that’s where the referees sort of came from and the referees were off the field of play at that time. They were a third party if you like that were only called into effect if the umpires couldn’t agree on a decision.

Walter Isaacson:

It didn’t take long before referees began to assume greater authority over the game. As the sport’s popularity grew, players, fans, club owners, and yes, gamblers too had a greater stake in the outcome. Increasingly, umpires found themselves unable to agree over calls.

Tom Webb:

As winning becomes more important, as there becomes more consequences for losing, then the role of everyone within the sport, within soccer, becomes something that people start to think about. Refereeing was no different. Clubs, players would start to look at it and think, “Well how good are these referees? Are they fit for purpose? Can we subsidize them? Can we look at how we train them?”

Walter Isaacson:

By the 1880s, referees were given the authority to award penalty kicks and even eject players from a game. Around this same time over in the US, baseball’s National League also introduced field officials into the game and as basketball and American football grew in popularity over the next few decades, they too began to introduce referees. The days of self-adjudication in sports were over, but traditions die hard in soccer. It took a very long time before officiating in Britain’s Premier League caught up with the modern world. As other sports embraced instant replay technology to help their officials make the right call, referees in the Premier League were largely left to fend for themselves. It wasn’t until 2019 that the league finally adopted a replay system called Video Assistant Referee or VAR. Howard Webb, no relation to Tom Webb, was a Premier League referee who retired in 2014.

Howard Webb:

I’ll be honest. I would have enjoyed using VAR. There’s occasions when I was reffing in the Premier League in big games that were being beamed around the world to millions and millions of viewers in addition to the 60,000, 70,000 people in the stadium and I would make a decision that was a close call, but I would also be aware that I could have got it wrong and that TV would be showing a replay within 10 seconds and that those millions on TV would know the answer that I didn’t have. The one person who needed to know the answer was me and I wouldn’t know it until after the game when it’s just too late by then.

Walter Isaacson:

Howard says one of the reasons why replays were so slow to arrive was that many soccer fans and officials worried that allowing referees to consult video replays would change the nature of the game.

Howard Webb:

Our sport is not a series of kind of set piece situations. It’s something that flows potentially for 20, 30 minutes at a time without a stoppage, but because there’s no obvious stoppages where things can be reviewed, I think there was also some difficulty in understanding how technology could be brought in without changing that basic way that the game is played. So it’s taken time to get enough body of support to say, “Look, the game can be enhanced. It won’t be damaged. It can still be a fast-flowing game without too many interruptions.” That’s another reason I think why technology was slow at coming in.

Walter Isaacson:

Today, video replays have been adopted by all major professional soccer leagues, but the rules governing when referees can request a video review are more restrictive than in most other sports. Video Assistant Referees will be part of the FIFA World Cup in Qatar in November 2022. It’s the biggest single sporting event in the world and FIFA officials are drawing on some innovative new technology to make sure those replays yield a correct and quick decision.

Paul Hawkins:

We now have full skeletal tracking. So we’re able to track 28 limbs of the body to know exactly where every limb of every player is.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Paul Hawkins, the founder of a company called Hawk-Eye.

Paul Hawkins:

We know which team everyone is which means that we can do offside automatically. So when we track the ball as well, we know when it’s kicked and we know where all the limbs of all the players are so we know immediately whether a player is offside or not.

Walter Isaacson:

If you watched a major tennis tournament in the past decade, you’ll be familiar with Paul Hawkins’ Hawk-Eye technology. Invented in 2001, it uses computers and sensors to determine where on the court a tennis ball has landed. The Hawk-Eye system has all but eliminated the often bitter argument between players and court officials that were once commonplace. Now, video replay can determine within seconds whether a ball is in or out with such precision that there is literally no room for argument. That same tracking technology is now being used in soccer to determine whether any part of the ball has crossed the goal line or if a player is offside. At the World Cup, Hawk-Eye will deploy as many as 12 cameras to track 18 points on each player’s body at 50 frames a second. It will triangulate all of that data to create 3D images of every limb of every player on the field. They’ll use it to establish if a player’s hand, leg, or elbow was offside or if the ball touched a player’s hand before it went into the net.

Paul Hawkins:

So that can get integrated into the replay system so that decisions can be made much, much quicker. It adds a little bit to the accuracy, but it’ll add a lot to the speed at which decisions are made.

Walter Isaacson:

Broadcast networks were the first to embrace the technology. Sports’ governing bodies followed several years later after extensive testing to ensure that it produced accurate results. Today, some variations of Hawk-Eye’s tracking and replay technology is used in more than 20 sports, but Hawkins doesn’t expect we’ll ever see the day when officials will be completely replaced by technology.

Paul Hawkins:

I can’t think of any sport where no humans are needed. Maybe less humans. Umpire and referee does so much more than just make the calls. There’s a real human side to being a good official in terms of player behavior and maybe the skillset of officials change so it does become a little bit more about man management and those soft skills rather than the technical skills of being able to make a call, but I can’t see a day when there are no officials in any of the sports that we’re involved with.

Walter Isaacson:

The technology that Hawkins developed had enhanced the viewing experience for fans and benefit officials both on the field and in replay centers, but there’s still more to be done. Other companies are working to enhance that experience even more. Hawk-Eye uses about a dozen cameras to create 3D images, but a San Francisco-based company called 4DReplay deploys up to 150 4K cameras throughout an arena to create remarkable 4D images in just a few seconds.

Henry Chon:

The core technology is that when camera one is looking at an object, the camera two and on look at that object exactly at the same time.

Walter Isaacson:

Henry Chon is a chief operating officer of 4DReplay.

Henry Chon:

So when you look at image one from camera and image two from camera two, you’re looking at the same object from a different angle, maybe three to five degrees apart. Right? So if you keep on doing that from camera one, two, three to all the way to 150, your eye starts thinking, “I’m looking at a video of going from this location smoothly turning around the object and coming back to the other side.”

Walter Isaacson:

Let’s say you’re at the ballpark watching a baseball game. A runner slides into home. There’s a close play at the plate. Is he safe or out? You can see the play from one angle at your seat. If the stadium is equipped with 4DReplay technology, you can pull out your phone and get a nearly instantaneous 360 degree perspective on that play and you can do the same thing if you’re watching at home.

Henry Chon:

You can pan left and right, zoom in and out, and time pause and forward and backward which gives you sort of better control of your watching experience.

Walter Isaacson:

The umpire also sees the play from just one angle. If his call is challenged by one of the teams, the replay center will review the play from several additional angles, but it’s not uncommon that their cameras still might not capture the one angle that allows them to make a definitive decision. Because 4DReplay covers that play from every possible angle, officials can make calls with a higher degree of certainty than ever before.

Henry Chon:

Our system can offer you within two seconds that actual moment from all the different angles. So officials are looking at the action from … Usually cameras are blocked or not blocked. So they’ll find an angle that they can see it without any obstruction. They’ll play it back and forth. They can zoom into the area of question and they can play that area back and forth or maybe they can look at it from a different angle. So they do all this and then they come up with a better decision.

Walter Isaacson:

4DReplay is currently available in two major league ballparks and Chon hopes to add his tech to more parks over the next couple of years. Major League Baseball first introduced instant replay in 2008. Now, close plays on the bases or at the plate are reviewable, but replays have proven to be a mixed blessing for baseball fans. There’s less of a chance that their favorite team will lose because of an umpire’s bad call, but having umpires consult with the replay center adds time to a game that many fans already believe is too long. The average length of a nine-inning game is now three hours and 10 minutes or about 20 minutes longer than it was in 2008. There’s also less action on the field. There are more strikeouts and flyouts and fewer hits and runs than ever before. To address that problem, baseball has been experimenting with new technology that could radically alter the game. Its official name is ABS which stands for Automatic Ball Strike System, but many fans refer to it as robo ump.

Morgan Sword:

The ABS system has three pieces to it.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Morgan Sword, the Executive Vice President of BASeball Operations at Major League Baseball.

Morgan Sword:

The first is tracking technology where a system of cameras installed around the ballpark picks up the pitch out of the pitcher’s hand and follows it until the catcher catches it. The second piece of the process is we have a piece of software that we developed internally that takes that pitch location that the tracking technology has produced and determines whether or not that pitch was a strike. Then the last piece of the process is that piece of software produces an audio signal that is relayed into the umpire’s ear. Then the umpire hears either ball or strike and then he can make the call on the field.

Walter Isaacson:

The official definition of baseball’s strike zone is a space above home plate between the batter’s knees and his belt. That seems pretty straightforward, but the reality is that umpire’s have always exercised a lot of discretion when it comes to calling balls and strikes. ABS will eliminate subjectivity from the process. It will also give Major League Baseball the chance to tweak the strike zone to reduce the number of strikeouts and increase the number of hits.

Morgan Sword:

We’ve thought about ABS as having two real benefits. I mean one is that you ensure a fully consistent and accurate ball-strike calling in all situations which I do think is a benefit, but the second thing is it allows you to pick a strike zone very specifically and change it over time depending on what types of adjustments players make to the ABS system. For example, we’ve learned in our Minor League testing that a strike zone that is slightly wider and slighter shorter vertically reduces strikeouts and creates more contact and puts the ball in play more. It wouldn’t be fair to ask human umpires to make those types of nuanced adjustments on a regular basis to the zone that they’re calling. When on the other hand if you’re using ABS, it’s literally a setting in the system that you just could switch overnight if you so chose. I think that as we look to create the most entertaining and action-filled version of our game, having that tool available to us is something that’s attractive.

Walter Isaacson:

By introducing ABS and adjusting the strike zone, Major League Baseball is trying to straddle the fine line between making the game more entertaining without altering its essential character. Given how often players argue an umpire’s call on the field, you’d think they’d welcome the consistency that ABS provides, but Sword says so far players seem to prefer human decision even with all their imperfections over machines.

Morgan Sword:

When you ask them why, one of the things you hear is that they actually really do like having the human umpire back there. They think that that’s the game they grew up playing, that’s the game that they have become good at it, and they like the ability in a challenge scenario to correct sort of the most egregious missed calls or the most impactful missed calls, but in general, have more deference to the umpire and his ball-strike calling. So that’s been their preference so far.

Walter Isaacson:

And what about the people most affected by the introduction of all of this technology? By and large, officials in all sports have accepted the need to relinquish some authority to a machine, but only up to a point.

Steve Javie:

The mentality of being a trained professional official no matter what sport it may be is to make a call and that’s what the profession expects and that’s what you’re trained to do and that’s basically your instinct. So it’d be almost taking away your officiating instincts.

Walter Isaacson:

Steve Javie began his officiating career as a Minor League Baseball umpire before switching to basketball. His first game as an NBA referee was in 1986 and over the course of the next 25 seasons, he was on the court for more than 1300 games. Today, he watches basketball from the NBA Replay Center in New Jersey where he provides rule analysis for viewers on ABC and ESPN. The NBA first used video replay to review last-second shots after the 2002 season. It’s a decision Javie says was welcomed by the league’s referees, including himself.

Steve Javie:

Prior to the NBA going to any sort of replay, I had a year or two where I must have had a half a dozen games where either there was a clock malfunction at the end of the game or we had really a close shot at the end of the game that would maybe be ruled correctly or incorrectly. I think the Rules in Competition Committee wanted to somehow try to incorporate a mechanism to try to get these plays called correctly. I was kind of relieved because I was like there’s a lot of pressure you’re on when there is no replay review or any kind of video to look at to confirm, say, especially like I said the game-ending, game-winning shot. So now, this took a little bit of pressure off the referees and I think we were kind of exhaling a little bit going like, “Good.”

Walter Isaacson:

The NBA now uses multiple cameras for their video reviews. It has also expanded the range of plays that can be reviewed to include many that have been notoriously difficult to call such as determining who last touched the ball before it went out of bounds. To help make those calls more accurate, the league is now experimenting with the same kind of limb-tracking technology that will be used at the 2022 World Cup. At the 2021 NBA Summer League in Las Vegas, Hawk-Eye installed 14 cameras in the rafters of the arena. Those cameras tracked players’ heads, hands, hips, and more than a dozen other body parts. They also captured the location of the ball in three dimensions with precision accuracy. The goal is to one day use that tracking technology to put an end to arguments over whose finger or foot last grazed the ball before it crossed the line or whether the ball left the shooter’s hand before the buzzer.

Walter Isaacson:

Javie says most NBA referees welcome these new additions to their technological arsenal. Anything that can prevent a game from being decided on a bad call is a step in the right direction, but he also points out that replay data from the NBA and other professional leagues consistently show that in the vast majority of cases, officials already make the right call without any assistance from technology. That’s sometimes hard to remember given all the criticism that comes their way from fans, coaches, and commentators. Technology, it seems, has made officials’ jobs easier and harder at the same time.

Steve Javie:

This is a game that’s played by imperfect people. All right? I’ll just think of basketball. If somebody shoots 50% for a game or the team itself shoots 50% for a game, it’s an incredible game, but they forget about the 15 or 18 turnovers they had or the missed free throws or the missed defensive assignments. The only place they really put perfection on is the official in any sport. I just think that the guys nowadays are put under so much pressure because of technology. I don’t think the game itself is as difficult to officiate, but I think it’s more difficult because of this technology of, “You know what? I ran it back and this 13th angle I saw, that referee missed a call and cost us the game.” So I think more pressure is put on the official from a technology standpoint of officiating than it is from the actual play itself.

Walter Isaacson:

When it comes to tracking technology that Paul Hawkins developed more than 20 years ago, it’s hard to think of a better description than game-changer. Hawk-Eye has improved the viewing experience for fans and it has brought a previously unimaginable level of certainty to decisions made by officials. These days when Hawkins thinks about the implications of his invention, he doesn’t focus on how it can help catch people who are doing something illegal. Instead, he prefers to think about a more innocent time long ago when players themselves would decide if rules were being broken. They didn’t need referees or umpires to tell them. That’s the world Hawkins would like to see arise again in sports and he believes technology could help get us there.

Paul Hawkins:

There are some instances where, because there’s technology there, players are more honest and they don’t take a dive because they know they’ll get called. They won’t get away with it. There are times when players in tennis will give the opposition a call because they know if it gets challenged, it will go against them. So I think that’s sports where people still show honesty and that character even when, under the greatest pressure and greatest determination to win and everything, that’s for me what sport is all about. When technology helps do that, I think it’s fantastic. I think it is great when the narrative of the game, what’s spoken about afterwards is about the sport and the players and not the officials. I think that’s really important and I think it helps send a really great message.

Walter Isaacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson and you’ve been listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies who believe there’s an innovator in all of us. If you’d like to learn more about the guests in today’s episode, please visit delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

An umpire and a manager arguing balls and strikes—it’s a scene as classic as baseball itself. But today’s technology can help ensure fully accurate calls and even adjust the strike zone. Innovation is taking hold in sports officiating and could literally change the game by speeding up play and decision making. Even sports like soccer that have been slow to embracing officiating are adopting technology to fully track players’ body parts and more. Multiple cameras follow balls and athletes across the field, enhancing the experience for the fans at home and in the stands.

An umpire and a manager arguing balls and strikes—it’s a scene as classic as baseball itself. But today’s technology can help ensure fully accurate calls and even adjust the strike zone. Innovation is taking hold in sports officiating and could literally change the game by speeding up play and decision making. Even sports like soccer that have been slow to embracing officiating are adopting technology to fully track players’ body parts and more. Multiple cameras follow balls and athletes across the field, enhancing the experience for the fans at home and in the stands. Henry Chon

is the Chief Operating Officer of the US Headquarters of 4DREPLAY. The company offers a ground-breaking media technology that has been revolutionizing the way various sports leagues officiate their games, including MLB, NBA, NHL, and many others worldwide.

Henry Chon

is the Chief Operating Officer of the US Headquarters of 4DREPLAY. The company offers a ground-breaking media technology that has been revolutionizing the way various sports leagues officiate their games, including MLB, NBA, NHL, and many others worldwide.

Morgan Sword

is the Executive Vice President of Baseball Operations at Major League Baseball. Originally hired in 2008, he oversees MLB’s competitive system, including all player acquisition, compensation and on-field issues including umpiring. He is a graduate of the University of Virginia and Columbia Business School.

Morgan Sword

is the Executive Vice President of Baseball Operations at Major League Baseball. Originally hired in 2008, he oversees MLB’s competitive system, including all player acquisition, compensation and on-field issues including umpiring. He is a graduate of the University of Virginia and Columbia Business School.

Tom Webb

is Senior Lecturer in Sport Management and Coordinator of the Referee and Match Official Research Network at the University of Portsmouth, UK. His research focuses on sports officials from multi-disciplinary perspectives. He has published two books and over 50 articles and book chapters on officiating.

Tom Webb

is Senior Lecturer in Sport Management and Coordinator of the Referee and Match Official Research Network at the University of Portsmouth, UK. His research focuses on sports officials from multi-disciplinary perspectives. He has published two books and over 50 articles and book chapters on officiating.

Paul Hawkins

is the founder of Hawk-Eye Innovations Ltd. Paul has taken the business from a start up in 2001 to a business which is now valued in excess of £250m. Andre Agassi described Hawk-Eye as “the biggest thing to happen in tennis for 40 years”. The technology is best known for its use in tennis, cricket and football but is also used in 24 other sports around the globe.

Paul Hawkins

is the founder of Hawk-Eye Innovations Ltd. Paul has taken the business from a start up in 2001 to a business which is now valued in excess of £250m. Andre Agassi described Hawk-Eye as “the biggest thing to happen in tennis for 40 years”. The technology is best known for its use in tennis, cricket and football but is also used in 24 other sports around the globe.

Howard Webb

is the general manager of the Professional Referee Organization and a former FIFA and EPL referee who became the first person to oversee both the UEFA Champions League and FIFA World Cup in the same year in 2010. In a career spanning 25 years, he also refereed the FA Cup Final (2009), the League Cup Final (2007) and the FA Community Shield (2005).

Howard Webb

is the general manager of the Professional Referee Organization and a former FIFA and EPL referee who became the first person to oversee both the UEFA Champions League and FIFA World Cup in the same year in 2010. In a career spanning 25 years, he also refereed the FA Cup Final (2009), the League Cup Final (2007) and the FA Community Shield (2005).

Steve Javie

is a retired professional basketball referee who officiated in more than 1500 games in the NBA between 1986 and 2011. Since 2012, Javie has been a rule analyst for the NBA and ESPN.

Steve Javie

is a retired professional basketball referee who officiated in more than 1500 games in the NBA between 1986 and 2011. Since 2012, Javie has been a rule analyst for the NBA and ESPN.