Walter Isaacson:

It’s November 6th, 2007 and 250 advertising execs representing some of the world’s biggest brands are packed into a Midtown Manhattan Loft. They’ve come to hear Facebook founder and CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, tell them how his platform is going to change the future of advertising. The event starts and the 23 year old Zuckerberg steps to the mic to address his audience. He says.

Speaker 2:

In the next 100 years, information won’t be just pushed out to people. It will be shared among the millions of connections people already have. Advertising will change. You will need to get into these connections.

Walter Isaacson:

Zuckerberg goes on to proclaim that recommendations from friends are quote, “The Holy Grail of advertising,” and Facebook has built a new tool that will allow companies to access this massive web of online connections. It’s called Facebook Ads. Facebook Ads will allow advertisers to connect with Facebook’s 50 million active users and target their advertising directly at them. Not only that, any engagement users have with brands on the platform, will be conveyed to everyone in that person’s social network through their newsfeed. Most ad execs in attendance that day, saw enormous potential in what the company was offering. Where else could they reach tens of millions of people with so little cost and effort? Where else could they get access to so much personal data and target their advertising so precisely?

But there are already problems on the horizon. One feature in the new ad platform is called Beacon, which automatically notifies a user’s friends when they purchase anything from a Beacon affiliated company. Understandably, many users are shocked and angered to learn that this information is being shared on the platform. A month later, Zuckerberg announced that Beacon would be scaled back and he apologized for not paying sufficient attention to users’ privacy. It’s a pattern that will become all too familiar over the coming years.

The introduction of social advertising back in 2007, set the stage for Facebook’s unprecedented growth and profitability. Today, its 3 billion active monthly users are targeted by just about everyone with a product or service to sell. But many people have come to believe that Facebook’s ad-based business model, with its singular focus on growth and engagement, has become hazardous to the health of both its users and society. They’re looking to reinvent social media by developing platforms where issues, like privacy and content moderation, are managed by the users and not governed by the priorities of shareholders and advertisers. 15 years isn’t a long time, except in the world of social media. I’m Walter Isaacson and you’re listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Speaker 3:

Ads are a small part of a much bigger problem. Fake users posting stories on Facebook, links on Twitter.

Speaker 4:

Social what?

Speaker 5:

Privacy, safety, and democracy. And you’ll rightfully have some hard questions for me to answer.

Speaker 6:

What we’re talking about is a cataclysmic change.

Speaker 7:

Made by someone who wants something. Remember this.

Walter Isaacson:

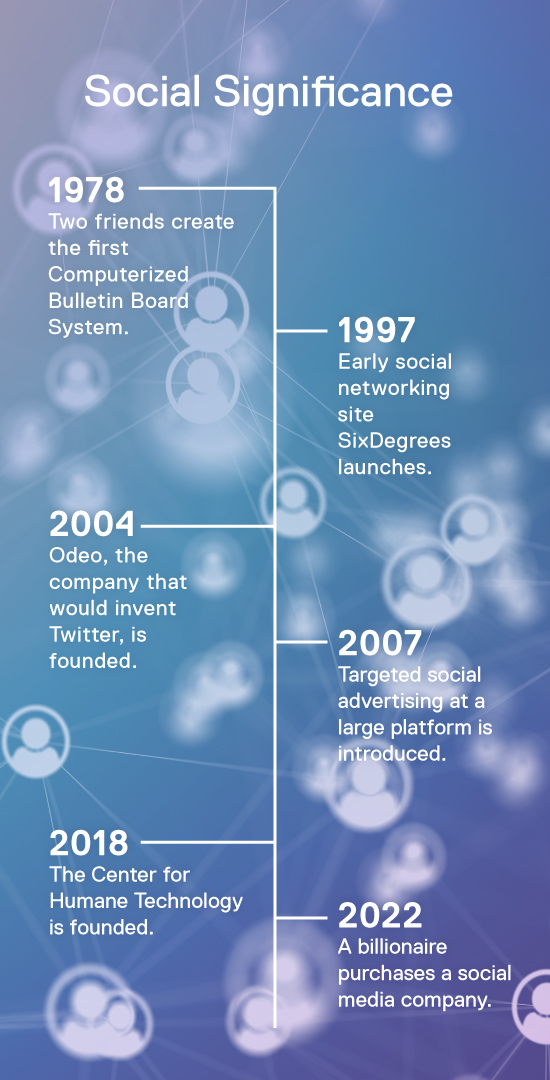

We have come to closely associate Facebook with social media, so it’s easy to forget that people have been finding ways to form online communities long before Mark Zuckerberg started his platform. In fact, the story of social media predates even the development of the World Wide Web. To find its origin story, you have to go all the way back to the 1970s, to something called BBS or Bulletin Board Systems.

Kevin Driscoll:

And at its heart, it’s a computerization of the community bulletin board, the same cork and pins kind of system that you would see in like the foyer of the grocery store where people can post notices and others can read them or reply or tear something off.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Kevin Driscoll. He’s the author of the book, The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media.

Kevin Driscoll:

And the Dial Up Bulletin board system was to take that idea and make it accessible over the phone line 24/7 to anybody with a computer.

Walter Isaacson:

Of course, in the 1970s, few people had computers in their homes, and only the most dedicated computer hobbyists had the dial op modems needed to connect to other hobbyists. So this being the lay of the land at the time, it makes sense that the first bulletin board system, was built by two of these hobbyists who were trying to figure out how to more effectively share information with other members of their community.

Kevin Driscoll:

It was the creation of two friends, Randy Suess and Ward Christensen, who were members of a local computer club. And they had the idea of making a online repository for the articles that they published in their club newsletter. And you really needed to be in a club or be reading these newsletters in order to get involved in home computing in the late 1970s, because a lot of these computers were built from kits by people soldering them together using Mimio craft instructions. And there were lots of ways it could go wrong and there was no way to search online for help. You needed to find other people who were doing the same hobby. So the bulletin board system was initially going to serve to become kind of like a library of a reference material for people building computers.

Walter Isaacson:

After setting up their BBS in Chicago in 1978, Suess and Christensen wrote an article describing what they had done for a popular computer publication called BYTE Magazine. Before long, thousands of local computer clubs around the country, were establishing their own bulletin board systems based on the Chicago model. Computer geeks loved BBS. Other people, not so much, because bulletin boards operated over phone lines, transmission of anything other than text, was cumbersome. They tied up home phone lines and could be expensive if users had to pay long distance charges. When the World Wide Web came along in the mid 1990s, most hobbyists were happy to leave their BBS behind, but their importance should not be underestimated. The modem world was a grassroots movement, with no centralized rules or authority. By contrast, social media, in the age of the Web, would come to be dominated by giant, highly centralized commercial platforms. And Driscoll believes there are important lessons that the BBS era can teach us about how to run successful online communities today.

Kevin Driscoll:

The platforms centralized control and really took away a lot of the capacity for people within the community close to the ground, close to the problems, to address them. So these became undemocratic spaces that don’t have opportunities for people to really affect change in their own community. And it’s such a shame, because when we look at this history of the modem world, we see that people were learning over tens of years, how to run successful communities and have people have voice in how things are run and operated and what works and what doesn’t work. And we’re not going to go back to the time of like when only computer geeks could get online, but they demonstrate that there were other models that worked to build communities that thrived and provided a lot of good to the people who use them. And we should be using those as resources to imagine better futures.

Walter Isaacson:

The consolidation of social media on platforms such as Friendster, MySpace and Facebook, didn’t happen overnight. In the early days of the web, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there were several attempts to keep the idea of decentralized social networks alive. The first was in 1997.

Andrew Weinreich:

I was an attorney at the time, the internet, the World Wide Web was taking off, and I had put together a group of people and we were looking for opportunities that we thought could uniquely thrive on the web. And I came up with this idea, which had been central to my life, of we could change the way people networked.

Walter Isaacson:

Andrew Weinreich was fascinated by how people turned connections into networks. We all have first degree connections, those are the people we know directly. And then there are some second degree connections, people we’re connected with through someone else. Think of setting up a friend with a blind date as a classic second degree connection.

Andrew Weinreich:

I was fascinated by this idea that you know 400 people, they each know 400 people, if there were no overlaps, that’s 160,000 people. That’s compelling. That is not a new thing, this paradigm or this dynamic of trying to interact with your second degree. What was new was the idea that I could get everyone to index their relationships in a single repository. If I could get everyone to say, “Put your Rolodex online, we’ll integrate them, we’ll validate relationships,” then I could accelerate the process of networking like it had never been done before. And that is essentially what a social network is. It’s your Rolodex online, with relationships that are validated on either end, by both parties. That is the sine qua non of every social network.

Walter Isaacson:

So Weinreich and his partners were a patent for how people could build social networks online. And they started a company to put their plan into action. They called it SixDegrees.

Andrew Weinreich:

In 1997, we threw a launch party at the Puck Building, downtown here in Manhattan. We had a big screen in front of the audience. I gave a talk and I said, “Here we are. We’re about to revolutionize the world. If you join this social network, you will one day be able to connect to everyone else. And to initiate this process, I am going to generate in front of all of you, an email that goes out to seven people.” Those seven people were people that worked at SixDegrees. An email went out to those people and it said, “Andrew is listing you as a coworker.” And those people confirmed, and as they confirmed, they were given an opportunity, either via email or the web, to list additional people. And so the idea, this is a distinction I’ve made over the years, was we became the first truly viral site.

Walter Isaacson:

Within a couple of weeks of its launch, SixDegrees was experiencing exponential growth, but an email based network proved to be very expensive to set up and maintain, and the company was sold in 1999. Weinreich has since gone on to start several successful companies, and thanks to SixDegrees, he’s widely considered to be the father of social networking, but not, he’s quick to point out, the father of social media.

Andrew Weinreich:

Our vision was not around social media, even though, yes, I hear that all the time that people refer to me as the founder of Social Media. Our focus was on social networking. Our focus was on extending human relationships, specifically for the purpose of making your life more efficient. That was our focus. And the consequence of that was that everything from on a personal level, feeling less isolated, to in a university, accelerating research and development, we believe all of that would be enhanced by this foundational element we were building. Part of our plan was not to create senseless content for people to consume. Now, it can be entertaining content. And so all content that’s developed on social media is not senseless, but that really was not part of our vision. It really wasn’t part of our intent.

Walter Isaacson:

While Weinreich was using the web to create social networks, to bring people together more seamlessly, others in the late 1990s we’re using online networks for political ends.

Evan Henshaw-Plath:

There was a political idea that we should be democratizing people’s participation in politics. It shouldn’t be a spectator sport.

Walter Isaacson:

Evan Henshaw-Plath, was a young politically active coder in 1999, when he attended the demonstrations against the World Trade Organization in Seattle. He was part of a group called IndyMedia, that did the first live stream of a political protest. Afterwards, he and several colleagues began thinking about ways of making media more participatory. In 2004, they created a podcasting company called Odeo. But when that proved unsuccessful, in true startup fashion, they pivoted. They began to think about how text messaging might be useful to communicate with larger groups. They had already developed something called txtmob, which was an activist text messaging system they had used during protests.

Evan Henshaw-Plath:

And we said, “Well, what if we made it a little bit more like blogging? What if we made it a little bit more sort of web based? What if we made it like short form?”

Walter Isaacson:

Web based, sort of like blogging, but shorter form? Does that sound familiar? It should because what Henshaw-Plath and his friends at Odeo were doing, was inventing Twitter

Evan Henshaw-Plath:

Every Wednesday for about six weeks, we’d get together at 9:00 AM, have a brainstorming, divide up into small interdisciplinary groups and work very hard. And then at 6:00 PM get together and demo what we built. What can you build in a single day? And that’s where Twitter comes from saying, “Let’s look at what we liked in the past. What is lightweight? What is new social? What is collaboration? What is keeping in touch with people? What is a status update? How do I know what’s going on? But how do I make it work on the phone? How do I make it work in an explicitly social way?”

Walter Isaacson:

In early 2006, employees at Odeo we’re using Twitter to communicate with each other, but with mixed results.

Evan Henshaw-Plath:

When we launched Twitter, it was just the dozen people at the office who were talking to each other. And we went out and signed up our friends, and half of our friends said, “This is completely stupid. Take it off my phone. I don’t want these messages.” And the other half loved it. The other half said, “This is amazing. I can know in an ambient way, what all of my friends are thinking and doing. And then you could tap into it.” And that’s a super addictive thing, of being able to sort of overhear the conversations of your friends and the thoughts of your friends. But we didn’t know that it was going to build a large audience. We didn’t realize it was going to be that transformational.

Walter Isaacson:

Twitter was introduced to the public on July 15th, 2006. In the first few months, the website was seeing about 20,000 Tweets per day. By 2010, there were 50 million. But by that time, Evan Henshaw-Plath and most of the original Odeo players, had left the company. Twitter was no longer an open, decentralized social network.

Evan Henshaw-Plath:

As Twitter grew, Twitter needed to raise money from the market in order to keep the servers going. Twitter needed to raise money in order to keep the lights on in order to fund the development. And early on, Twitter worked much more like email or the web. And the work of keeping it online and keeping the servers up and keeping it scaling, that work meant that the focus on this open network and these open protocols, dropped away. And Twitter lost that thing that made it of everybody. And so, I would say that in many ways, it was the market that saw this thing as a valuable piece of real estate and attempted to take it over that caused Twitter, the company, to lose a bunch of its openness. And Twitter became more of a regular company. It became more of a platform as opposed to this open space.

Walter Isaacson:

Twitter’s roots were bright eyed and idealistic, but as the company quickly scaled, it evolved into something different, than Henshaw-Plath first envisioned. It’s a common trajectory of the social media platforms have followed as well, including Facebook.

David Kirkpatrick:

I remember the very first time I ever met him, which was in early September, 2006, and I said to him, “You seem like a natural business person.”

Walter Isaacson:

This is journalist David Kirkpatrick.

David Kirkpatrick:

And his face scrunched all up and he acted really offended that I had said that. And he adamantly insisted, he didn’t do this as a business, he just thought it was something cool.

Walter Isaacson:

Mark Zuckerberg was just 22 years old the first time he and Kirkpatrick met. And the cool thing that the young Zuckerberg was being interviewed about, was his new social networking platform, called Facebook.

David Kirkpatrick:

My first impression was that he was absurdly young and what was I doing as a serious minded Fortune magazine reporter, wasting my time with somebody who was such a juvenile? I mean, honestly, he walked up, he looked like my grandson or something. But as I always say, that didn’t last very long. All he had to do was open his mouth and I started to pay serious attention. Essentially every word he said was the language of a deeply committed, serious, business thinker who didn’t happen to think of himself that way, but who was thinking strategically, thinking long-term, thinking through the eyes of the customer. Highly ambitious. Wasn’t joking around at all.

Walter Isaacson:

In 2010, David Kirkpatrick wrote a bestselling book called The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company that is Connecting the World. It offered a positive spin on the company and its founder, who the author portrayed as both a savvy businessman and an idealist. Kirkpatrick felt Zuckerberg, really did want to use the power of social networks to bring the world closer together. But in the years following the publication of his book, Kirkpatrick has gone from being one of Facebook’s biggest fans, to one of its harshest critics.

He still believes that Facebook continues to make many positive contributions to the world, connecting people in ways that had never before been possible. But as Facebook’s focus shifted from social networking to social media, he believes the company lost its focus. Kirkpatrick blames Zuckerberg for being so relentless in his pursuit of growth, that he became willfully blind to the mountain of evidence that his platform was being used to funnel political disinformation. Rather than bringing the world closer together, it was helping to tear it apart.

David Kirkpatrick:

He really does believe that it’s not his responsibility how people behave. And even though he’s running a commercial product, he thinks of it more like a public utility. He thinks of it sort of like a neutral platform that is not his responsibility, that if people come on there and advocate hate or violence or suicide or propaganda, that’s just what people do, and he shouldn’t be blamed for human nature. That’s his general stance, which is wrong in this case, in my view, because it is a commercial product. He does control the levers. He is essentially a publisher. And by disregarding any substantial responsibility for governance and oversight, he is committing what I would actually say, is a moral crime.

Tristan Harris:

We now have a situation where when starting in the early 2000s, as all these companies were coming up, Facebook, Twitter, Google, YouTube, Snapchat, TikTok, are all in this zero sum competition for attention. If I don’t get that attention with whatever means necessary, I will lose to the companies that do use the means necessary.

Walter Isaacson:

Tristan Harris was a design ethicist at Google in 2013, when he wrote a presentation calling for designers to be less focused on trying to grab users’ attention. He spent two years preaching that message inside Google with little success. So in 2015, he left the company and started the Center for Humane Technology.

Tristan Harris:

The whole premise of our work is the idea that we can have humane technology that actually operates in humanity’s best interests and strengthens the core life support systems of society. Can strengthen democracy, can strengthen children’s mental health, can strengthen the development of a society and our wisdom and the kind of culture that we need to operate in.

Walter Isaacson:

Harris pulls no punches when he talks about the harms being caused by the big social media platforms. He believes that their obsession with growth and capturing users’ attention at all costs, forms an existential threat to the health and safety of individuals and society as a whole, contributing to the problems of addiction, social isolation, and even suicide.

Tristan Harris:

The phrase that we use to describe this with, the way that technology has been hijacking more and more of human vulnerabilities, is that this causes a race to the bottom of the brain stem. Who can go lower into our limbic system? Who can go lower into creating habit formation, addictive loops, dopamine activation, social validation, social pressure, social anxiety, social visibility? The more of those levers of the human mind that I can activate, I will simply out compete the other actors that use fewer of those levers or the less powerful of those levers. And so that’s the fundamental race. That’s where it all went wrong, is this attachment to growth and engagement. And if you change that, you can actually have technology that is operating in our best interest.

Walter Isaacson:

But can social media really be changed to make it more humane? Are there other ways of connecting people online that might mitigate the harms that Tristan Harris and others have been warning about? And will the big platforms that have dominated social media over the past decade, be part of the future? All of them are facing challenges. The future of Twitter, under the leadership of Elon Musk, is unclear. TikTok, a short form video hosting service, has seen explosive growth over the past few years, and there are concerns about how and where it’s sharing the vast amounts of data it collects from users. And then there’s Facebook.

In October, 2021, Facebook rebranded as Meta. Mark Zuckerberg has invested billions of dollars to create the Metaverse, a virtual immersive world where people can live, work, shop, and interact with others, without having to get off their couches. Will Zuckerberg’s big bet pay off? Andrew Weinreich, the founder of SixDegrees, isn’t convinced.

Andrew Weinreich:

First of all, I’m not sure I’m a believer in the Metaverse to begin with, but to the extent I do believe that there’s something there. Do you think innovation will come from startups or do you think it’ll come from a big player like Facebook that’s invested $16 billion to date? No, from startups. We’ve seen that. We have 25 years of social networking to look back at. And the only certainty we know is that at the moment of certainty that a company enjoys dominance, a startup comes and completely disrupts them. That’s the only certainty we have, that it’s a false certainty. So I don’t know why we wouldn’t expect that to continue.

Walter Isaacson:

Evan Henshaw-Plath, the man who helped invent Twitter, also does not believe that the future of social media lies inside any of the existing mega platforms. That’s why he started Planetary, a decentralized, open source, peer-to-peer network, that’s controlled by its users.

Evan Henshaw-Plath:

Planetary is a tool for people to have their own voice and control their own forms of communication. And it’s not perfect. And there’s going to be terrible stuff on there as well. But you’re not dependent on someone else enforcing the rules. We give you the tools to make and enforce the rules yourselves.

Walter Isaacson:

And he thinks the future of social media will look very much like its past.

Evan Henshaw-Plath:

Planetary is an attempt to get back to the idea that what we have here is a commons. What we have here is a public space, that isn’t owned and run by any one thing. And what became on Twitter was more like a shopping mall. It feels like public space, but it’s actually privately run corporate space. And so what we’re building with Planetary is sort of reviving that dream. It’s an open protocol. You can have privacy, you can do things in public. Everything’s controlled on your phone. You don’t have some third party algorithm deciding what you can see. You can see what algorithms are going to control your timeline and choose different ones. So it’s about user empowerment, it’s about community control, and it’s about saying that this social media space, should be a commons that needs to be well governed.

And right now we have a thing where a few billionaires get to decide what our environment looks like. What speech is acceptable. Who can reply to us. What content we see. And I don’t think that that should be the decision of any small group of people. I think that we need to decide for ourselves what kind of social spaces we have.

Walter Isaacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson, and you’ve been listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies, who believe there’s an innovator in all of us. If you’d like to learn more about the guests on today’s episode, please visit delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

For many people, the act of connecting with friends, family and groups of like-minded people is dominated by certain large social media platforms. Though there are a few sites and apps that are ubiquitous today, people have been experimenting with different forms of digital social networks since the 1970s—before personal computers were mainstream. Now, some people are looking outside of the major platforms and building decentralized, open-sourced networks that take their cues from the early days of social. Will the next wave of social media look more like its past? Listen to find out on this episode of Trailblazers.

For many people, the act of connecting with friends, family and groups of like-minded people is dominated by certain large social media platforms. Though there are a few sites and apps that are ubiquitous today, people have been experimenting with different forms of digital social networks since the 1970s—before personal computers were mainstream. Now, some people are looking outside of the major platforms and building decentralized, open-sourced networks that take their cues from the early days of social. Will the next wave of social media look more like its past? Listen to find out on this episode of Trailblazers.  Andrew Weinreich

is a serial entrepreneur and social networking pioneer. In 1996, he launched Sixdegrees.com, the world’s first online social network, which grew to become one of the largest community sites on the Internet. @andrewsroadmaps

Andrew Weinreich

is a serial entrepreneur and social networking pioneer. In 1996, he launched Sixdegrees.com, the world’s first online social network, which grew to become one of the largest community sites on the Internet. @andrewsroadmaps

Evan Henshaw-Plath

is the founder of peer to peer social media app planetary.social and was the first employee and lead engineer at the company that created Twitter. @rabble

Evan Henshaw-Plath

is the founder of peer to peer social media app planetary.social and was the first employee and lead engineer at the company that created Twitter. @rabble

Kevin Driscoll

is the author of The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media, co-author of Minitel: Welcome to the Internet, and maintainer of the Minitel Research Lab, USA with Julien Mailland. He is an associate professor of media studies at the University of Virginia. @kevindriscoll

Kevin Driscoll

is the author of The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media, co-author of Minitel: Welcome to the Internet, and maintainer of the Minitel Research Lab, USA with Julien Mailland. He is an associate professor of media studies at the University of Virginia. @kevindriscoll

Tristan Harris

is Co-Founder & President of the Center for Humane Technology, which is catalyzing a comprehensive shift toward humane technology that operates for the common good, strengthening our capacity to tackle our biggest global challenges. He is the Co-Host of “Your Undivided Attention,” which explores how social media’s race for attention is destabilizing society and the vital insights we need to envision solutions. @tristanharris

Tristan Harris

is Co-Founder & President of the Center for Humane Technology, which is catalyzing a comprehensive shift toward humane technology that operates for the common good, strengthening our capacity to tackle our biggest global challenges. He is the Co-Host of “Your Undivided Attention,” which explores how social media’s race for attention is destabilizing society and the vital insights we need to envision solutions. @tristanharris