WALTER ISAACSON: A quick note before the show starts. We’re planning new episodes of Trailblazers right now. And as we do, we’d love to know your thoughts. We’ve put up a short survey at our website, Delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. And if you have the time, the whole survey only takes a couple of minutes and will really help us out. Again, that’s Delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. And now, on with the show.

It’s 1959, and a new chapter in the search for human intimacy was about to be born. And it would happen in a place that not too many people in the world associate with being the epicenter of romance, the mathematics department of Stanford University.

For their decidedly unromantically titled computer course, the theory and operation of computing machines, Phillip Feiler and James Harvey needed a final project that would employ Stanford’s new state of the art punch card computer. They called their project “The Marriage Planning Service.”

First, they created a pool of 49 men and 49 women, and asked each to take a survey. Among the questions– do you consider yourself an introvert or an extrovert? Are you patient or impatient? Are you affectionate or unaffectionate?

These insights were fed into the computer, which took six hours to correlate the data, a process that would take today’s laptop about two milliseconds. Based on the survey, the computer generated the best match first, then the second best match, and on down the line. The last man and woman to be paired– a Stanford freshman with a 40-something single mom. The project got an A anyway.

The effect of those two Stanford undergrads, as well as a handful of other digital pioneers, cannot be overstated. From that day on, the combination of desire and the power of digital technology would disrupt humankind’s eternal search for the perfect match, in ways never imagined. I’m Walter Isaacson, and this is “Trailblazers,” an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

MAN: You young punks go to the movies a couple of times, do a little necking, and you think you’re in love.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MAN: How do you choose a date?

MAN: Just me and a girl.

WOMAN: They began to go to secluded places, and their relationship became more intimate.

MAN: Will they be companions as well as lovers?

WOMAN: Take my advice, think twice before you start going steady.

WOMAN: I’ve been in love several times before.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

WALTER ISAACSON: Who knew that the secret to finding that special someone would be guacamole. According to the dating site, Zoosk, those mentioning food in their dating profile are more prone to attract messages. The word chocolate boosts responses by 100%. Mention of potatoes causes 101% increase. And mention that magic word, guacamole, and see your desirability increase by a whopping 144%.

Zoosk examined four million dating profiles and surveyed 7,000 people to learn more about how food connects to dating. Just as medieval cultures created love potions from Mandrake roots, beetle wings, and worms, today’s purveyors of amore are turning to big data. And with one in five Americans actively using dating sites and apps, there’s plenty of source material.

Not surprisingly, Zoosk declines to explain these findings. As with so much big data, it’s all about the what , but much less forthcoming about the why. Though still in its infancy, today’s multi-billion digital dating industry is changing the way people connect, and even the nature of relationships. Yet, it’s just the latest chapter in the story of how commerce and technology have shaped the ancient art of matchmaking.

The first technology to effect massive change on matchmaking and courtship was the printing press. The printed word begat newspapers and classified ads. Boy meets girl met ink and broadsheet. As early as 1695, England’s first classified ad appeared.

MAN: 30-year-old gentleman with a very good estate searching from some young good gentlewoman that has a fortune of 3,000 pounds or thereabouts.

WALTER ISAACSON: By the 1900s, long before the farmer’s only dating app was a gleam in its developer’s eye, mail order brides helped populate America’s West. Following the San Francisco gold rush, an opportunistic publisher created the “Matrimonial News.” for $0.25 a man could place an ad seen by single women all over the country. Ads were free of charge to women.

Even so, few young ladies would expect to marry without the blessing of their family. That is, until the early 20th century, when an urban economic shift would change the tradition of courtship. Moira Weigel is a writer, scholar, and founding editor of “Logic,” a magazine about technology and culture.

Moira Weigel: What’s really distinctive about dating, and what I call the invention of dating, is this move from private family, community controlled spaces to market spaces, and public spaces, and everything that comes along with that. So if we think of like the Jane Austen scenario, when you’re sitting at home in your parlor, your mom, or your aunt, or your sister is there. Some new guy came to town. He can expect 100 pounds a year or whatever it is.

All the incentives are aligned. The platform of courtship is the family home. It’s supervised by parents. And the people who own the platform, and are supervising your courtship, have an incentive in seeing you paired off well.

WALTER ISAACSON: That all changed as courtship moved outside the family home and beyond the jurisdiction of controlling parents.

Moira Weigel: Once dating moves into public and market spaces, the people who own the platform do not have that incentive. The guy who owns the boardwalk, or the movie house, or the dance hall, if we’re talking about the late 19th, early 20th century, when these practices first developed, does not have the same interest in seeing you pair off with someone that your mom did. And in fact, has the opposite interest.

It’s much better for the owner of the bar, economically, if nobody ever pairs off and stays home with kids, right? They want everyone to keep coming to the bar. And so there’s this deep fact in the DNA of dating, that when courtship moves from private and family controlled spaces to market spaces, it produces this gap between the interests of people who are theoretically trying to seek life partners or to pair off, and the interests of the owners of the platforms.

WALTER ISAACSON: And it’s this gap, between economic interests and romantic interests that would go on to shape the dating industry right up until today. Many dating services may market themselves as a quick, easy, and even fun way to meet your soulmate. But the true business model behind many is to keep the user engaged, funding those services for as long as humanly possible.

And it was under this notion of the power of repeat customers that the economy of fix ups was born. Let’s skip ahead a bit.

MAN: The only thing we have to fear is–

WALTER ISAACSON: Keep going.

MAN: God speed, John Glenn.

WALTER ISAACSON: A little more. There, to 1964, five years after those Stanford undergrads dabbled in digital matchmaking. If you were to cast the role of the pioneer in commercial computer dating, you could be forgiven for overlooking England’s Joan Ball.

She’d been physically abused by her mother, estranged from her parents, and institutionalized. At 19, with no home to return to, she worked as a shop clerk before taking a job at a marriage bureau, a non-digital matchmaking service. Marie Hicks is an assistant professor of history of technology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

MARIE HICKS: She found that she had a real knack for doing this sort of work and so she set up her own marriage bureau. And within a year or two, she started to realize that these sort of very individualized, bespoke match ups, where she was putting a lot of labor into matching people up, she needed help with that. And so she decided to automate it.

And that’s where she came up with the whole premise for a computer dating business. And it was so successful, even just the first run, that she actually changed the name of her marriage bureau to reflect the fact that it was now a computer dating business.

WALTER ISAACSON: The new name was Com-Pat, a conflation of computer and compatibility. Unlike the primitive computer dating of the time, Joan Ball infused the process with the insights she gained working with the marriage bureau.

MARIE HICKS: Unlike so many other people, especially so many other young men, who started computer dating businesses in the ’60s, and in the ’70s, she actually had experience as a matchmaker. She actually had experience trying to match people up and deal with their desires, and deal with what they didn’t like, and try to figure out how to get people together in a humane way. And she built that into her computing system.

WALTER ISAACSON: For Joan Ball, promoting her new business was an uphill climb. She was a female entrepreneur in a culture that didn’t yet place a value on that. Worse still, conventional ad media wouldn’t stoop to run creative for a business so tawdry as computer dating. That didn’t stop Joan Ball.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

She took her advertising offshore, to another group of social outliers, pirate radio stations operating on ships off the coast. These so-called pop pirates transmitted from international waters, playing the new rock and roll music that the BBC wasn’t ready to allow.

MARIE HICKS: Joan Ball thought, oh, well, if regular publications who are so concerned about the appearance of impropriety won’t take my ads, what if I advertise with the pop pirates. And so she did. And I think that really was a smart move. Because she was advertising with people who were similarly iconoclastic, similarly on the cutting edge, and it was likely to reach an audience of people who were more likely to use her business.

WALTER ISAACSON: Meanwhile, 3,200 miles to the east, a small group of Harvard undergrads was creating a computer dating venture of its own, but with a decidedly different motive. Marie Hicks–

MARIE HICKS: They just sort of came up with this idea. And the reason they came up with this idea was because they absolutely hated going to college mixers, so like going up the road to Radcliffe and standing around clutching a drink for an evening, and trying to meet women. They said that the college mixer there was a particular social evil.

And so they were trying to get women without all the hassle of having to go through the trouble of actually meeting them and talking to them. That’s how they were going to short circuit things. They were going to use a computer.

WALTER ISAACSON: They called their computer dating service Operation Match. For $3, customers filled out a questionnaire answering twice, once for themselves, and again for their ideal date.

DOUGLAS GINSBURG: Then it was promoted very much as a lark. See who your ideal date would be.

WALTER ISAACSON: Judge Douglas Ginsburg is a US circuit court judge, and a former nominee to the Supreme Court. But back in the mid-60s, he was a university drop out, who had joined forces with the Harvard undergrads to run Operation Match.

DOUGLAS GINSBURG: And we had the data key punched into cards. The data were actually sent to Korea, to a service bureau there that did the card preparation. Brought back to the US, and we contracted with a computer servicing company to run the programs that we had written in order to get the best matches from among the participants.

WALTER ISAACSON: The company became a cause celebre, and was widely, and incorrectly, celebrated as the world’s first computer dating company.

DOUGLAS GINSBURG: We had tremendously good reception among students and got some very good publicity, including a cover in “Look Magazine,” and so we rolled it out nationally the following September. And that was really a big turning point for us. We had every prospect of being a successful national and enduring company, which didn’t happen.

WALTER ISAACSON: In time, Ginsburg and his colleagues sold their interests in Operation Match. While in England, Joan Ball’s Com-Pat lasted 10 years before she sold out to her corporate arch rival, Dateline. These computer dating pioneers created platforms for meeting. And did their best to create match algorithms.

More importantly, they warmed the culture to the idea of digital dating. None of them foresaw the scale of the revolution that was still to come.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

If you can’t remember whether you’ve met Gary Kremen, then you haven’t met him. He’s an energetic, shamelessly confident, software pioneer, with a Standford MBA and a knack for disruption. As a student, he was given an internship at Goldman Sachs. Just three weeks in, a Goldman executive offered to buy out the rest of his summer wages if he would leave immediately.

In the early ’90s, Kremen ran a small software company in Silicon Valley. He also ran up a sizable tab calling 1-900 dating numbers, in those days a product of newspaper classified ads.

GARY KREMEN: Yeah, so the business model back then is newspapers would publish you know single, white, male seeking blah, blah, blah– usually a single white female in the heterosexual dating world. And then you would contact that person by calling a 900 number. And your phone would get billed for it. And you would leave a message, and hopefully someone would call you back. And I would get bills of like $50, $100.

WALTER ISAACSON: Kremen believed he had a better idea, to create an online classified ad service.

GARY KREMEN: So I took a cash advance on my credit card, moved from like the Palo Alto area up to South Park in San Francisco. And I started writing software for this idea, that people could fill out a form in email, send it into my computer program, and it would match them up with people. That was kind of the genesis.

So the first incarnation of– let’s call it internet dating, but it was still email, was based on email. You’d fill out a form. Our little program, my program would parse it, find a match for you, and maybe send back the information on their form. And potentially, with a picture.

WALTER ISAACSON: In a time when web domain names were free, Kremen acquired the rights to some of the world’s most valuable URLS, including jobs.com, autos.com, housing.com, and even sex.com. For this venture he obtained Match.com. As the company expanded to offer both email and web-based services, the next challenge was marketing.

GARY KREMEN: So I had this idea that– I’ll call it influencer marketing. The best way to market was– I realized that given the lack of women online, they were the people. So we only marketed to women. And we marketed to women’s influencers. Who would influence women online? Maybe in academia, or business, or other things.

So we – I hired a woman general manager, a classmate of mine, who figured out let’s do some brand management and just focus on women. Interview, we interviewed over 100 women and asked them what they would want. And you have to understand, at the time, putting your profile, your personal information, that was a radical idea. People thought I was crazy, that, oh, no one would ever put their heart online, no one would ever do that. But I had a feeling that, if you think of the Maslov Hierarchy of Needs, love is up there.

WALTER ISAACSON: In 1995, as the brand gained traction, Gary Kremen experienced what some would call a John Lennon moment.

GARY KREMEN: They pushed me to go do interviews. And it made sense. Articles would come out, and then people would maybe read about it. Although, the amount of people who would be reading a story, and the amount of people on the internet was a small set together. But I used to have less caution than I did.

And I did see the vision for people meeting each other online and how big online dating would be. So I said that we’re going to create more love than Jesus Christ. And I got a lot of flak from my investors. The beginning of me and my investors not getting along well.

WALTER ISAACSON: Yet, it wasn’t his invoking Jesus’s matchmaking prowess that ended Gary Kremen’s run as CEO of Match.com. Rather it was his vision for who might use it.

GARY KREMEN: Yeah, so I was a believer that relationships and love is a wide spectrum, and everyone deserved love and relationships. So I, being in control for a little while at least, of everything, I changed it from just long-term dating, to maybe, let’s call it short-term dating, from heterosexual dating to inclusive. First LBGTQI dating. And we marketed in that area. And that really got the investors really frazzled up. I won’t say they were homophobic, but maybe someone else would say that.

WALTER ISAACSON: There was also a difference over business strategies that marked the end of the first incarnation of Match.com.

GARY KREMEN: They wanted to sell this technology to newspapers. And I knew that was a bad idea, because I went to go talk to newspapers, and I saw how slow and conservative they were. And I kind of had a feeling they were road kill, which is what happened.

And they wanted to sell technology and power their classified advertising. And I said absolutely not, that’s never going to work. And they said, yes, it’s going to work, and we don’t want this embarrassing dating thing. So they sold it to a company called Cendant for $7 million, who nine months later sold it for $50 million.

WALTER ISAACSON: Gary Kremen even found his own match. But it wasn’t through Match.com, or any other dating site.

GARY KREMEN: That’s true. How I met my former wife was– through I offered a reward. Because I understand people’s motivation. So I offered a trip to Hawaii for two for the person who set me up with the person I would marry. And that worked out. So I did believe– I learned a little bit about customer acquisition and lead generation.

WALTER ISAACSON: True to Gary Kremen’s vision, dating sites gradually began filling those niches. New dating sites emerged based on race, and color, body type and faith. Then a decade ago, a new technology was introduced. And at long last, online dating found its digital soulmate– the app.

Their impact on dating has been transformative. Mobile apps provide portability, ease, the benefits of geolocation, and anywhere, anytime connectivity. Which according to writer Moira Weigel may be a blessing and a curse.

Moira WEIGEL: I think that it’s really hard to separate how mobile apps are changing romance from all these other factors that are also changing romance. But I do think that it’s making romance more flexible for good and for ill. The thing that’s important to that, at like a human level for romance, I think, is to remember that these apps are designed to get us to process as many people as possible, which may not be what we want as humans.

After the digital revolution, we may be in for a different form of romance and family formation. And maybe that’s great. But it’s certainly true that in tandem with the rest of the platform economy, the apps are changing courtship too.

WALTER ISAACSON: Studies show that people who once spent hours gazing down a bar now spend that time fine tuning their online dating profile. An article in “The Atlantic” tells of women who spend 10 to 15 hours on online dating each week in order to generate one date.

At the epicenter of these apps is Tinder, credited for the gamification of dating. Profiles are photo-based. Swipe right if you like someone. Swipe left if you don’t. Block someone, message someone else. And unlike conventional person to person venues, no courage is required. Users only know when they’ve been approved, not when they’ve been rejected.

Moira WEIGEL: I think that there is something really qualitatively new about mobile dating apps, and particularly about the way in which they make it possible to be looking for love all the time. I often hear people talk about the sense that dating is work, it’s something that people feel an obligation to do.

And like all the rest of our work lives, now that we have computers in our pockets and in our beds 24 hours a day, it’s something people feel compelled to do all the time. So I think that the shift to mobile dating platforms is this sense of 24/7, constant shopping, constant shopping around, constantly trying to sell yourself, and feeling that that never turns off.

WALTER ISAACSON: And therein lies the disruptive magic of the dating app. They promise the prospect of intimacy with others. Their business model depends on you forming a relationship with the app itself. And unlike going to the bar to try to find your soulmate, dating apps never close for the night.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Just as dating radically changed the rituals of courtship more than a century ago, digital technology has already changed dating forever. As it does, the very definition of the word dating grows more opaque. To some, it’s about marriage. For others, it’s recreation. For some, it’s platonic. To others, decidedly not. And for some, it’s about the simple dopamine hit of knowing someone right swiped their profile picture.

The desire for intimacy is as old as humanity itself. Online dating reminds us that the tools we use to find it are constantly changing, and in turn, changing us. But maybe some things don’t change. A little guacamole never hurts.

I’m Walter Isaacson, and this is “Trailblazers,” an original podcast from Dell Technologies. For more information about the business of dating, visit our website, Delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. And join us for the next episode, where we’ll be looking at the business of space and how Silicon Valley is beating NASA at its own game. Until then, thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Desperately seeking someone

Desperately seeking someone Algorithms as matchmakers

Algorithms as matchmakers The dot-com of desire

The dot-com of desire The people we want. The apps we adore

The people we want. The apps we adore Moira Weigel

Is a junior fellow at Harvard University and the author of Labour of Love: The Invention of Dating. She is a co-founder of Logic - a magazine about technology.

Moira Weigel

Is a junior fellow at Harvard University and the author of Labour of Love: The Invention of Dating. She is a co-founder of Logic - a magazine about technology.

Marie Hicks

Is an assistant professor of history technology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research focuses on how gender and sexuality bring hidden technological dynamics to light.

Marie Hicks

Is an assistant professor of history technology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research focuses on how gender and sexuality bring hidden technological dynamics to light.

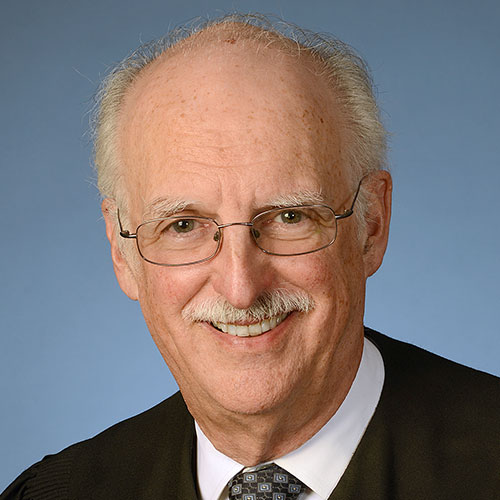

Douglas Ginsburg

Is a Senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals. In the mid-1960s he helped found one of the first nationwide computer dating services, Operation Match.

Douglas Ginsburg

Is a Senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals. In the mid-1960s he helped found one of the first nationwide computer dating services, Operation Match.

Gary Kremen

Is an engineer, entrepreneur and founder of several companies, including the online dating site Match.com.

Gary Kremen

Is an engineer, entrepreneur and founder of several companies, including the online dating site Match.com.