By Anne Miller, Contributor

A blind woman in a wedding dress wanted to check for stains before she walked down the aisle.

In Finland, a mother who couldn’t see her son’s first basketball game hoped for someone to describe it to her.

Others need help troubleshooting computer problems with a help desk — it’s not easy to fix errors when you can’t see a software-failure message.

Too often, notions of helping the blind involve poring over a braille text or crossing the road (which many people with vision impairment navigate just fine, thanks). Sometimes, though, people need the most help with the mundane details of modern life.

Global, Social Eyes

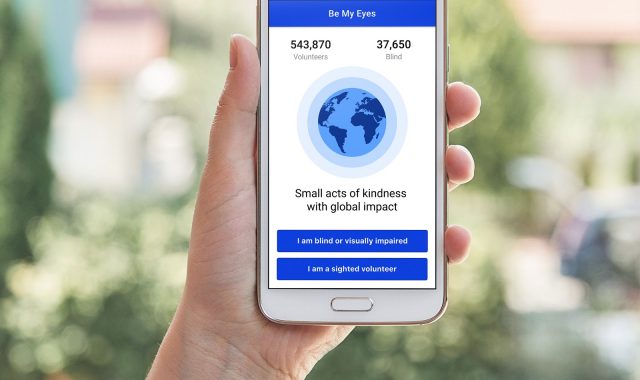

Be My Eyes, a successful Danish startup mobile app, aims to fill this aid gap. It offers sighted volunteers a chance to “be the eyes” for those who can’t see using their smartphones — a global social-media platform of eyes for the blind. The app’s founder, Hans Jørgen Wiberg, is visually impaired, and through his own experiences realized that sometimes the little things require the most pressing assistance.

Launched in 2015, Be My Eyes connects blind users with sighted volunteers via smartphone video capability. The requests tend to be easy yet vital, like reading the expiration date on a milk container or the dosage on a vial of medicine.

“Since launch, everything kind of exploded,” Alexander Hauerslev Jensen, Be My Eyes’s community director, said. He is stationed in Silicon Valley now, to better connect his firm with tech investors, but his Scandinavian accent remains thick.

“All of us are Danish, and maybe our ambitions were as small as the country we are from,” he joked. “At first, we were like, ‘After three months maybe we expand out of Denmark, into Sweden.'”

Instead, within 24 hours of launch, their app was downloaded in 30 countries.

“We said, ‘We might be on to something, ya?'”

Seeing Viral

Some 49,000 blind users have downloaded the app, while another 600,000+ sighted volunteers have, too. If users need help, they put out a call on the app, which goes to people who speak their language and are located near their time zone. The idea is that someone in Australia who needs help, for example, isn’t waking up an American before dawn. Volunteers claim the call, which starts a video chat.

“At the beginning, we wondered if we needed to pay volunteers, but now there’s something very pure and very human and very nice about helping someone you don’t know,” Hauerslev Jensen said.

They aim to keep things simple. “Everything is designed with one thing in mind, which is accessibility,” he said. “A lot of apps are trying to put in more and more stuff, to make them better. For us, we are trying to keep it super simple.”

Too often, says Will Butler, the media and communications officer at LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired, a Bay Area nonprofit that provides consulting and services to the blind community, companies want to solve logistics around a sighted world without actually talking to blind people to understand how they experience it.

“Be My Eyes is one of a lot of different tech companies who have come to us, mostly for user testing and to get feedback,” he said. Yet, for Butler, many of these companies miss the mark in serving the blind because they focus on what sighted designers think the blind need.

“At the beginning, we wondered if we needed to pay volunteers, but now there’s something very pure and very human and very nice about helping someone you don’t know.”

— Alexander Hauerslev Jensen, Community Director, Be My Eyes

“People are always trying to put stuff on our canes or replace our dogs,” Butler said. “They’re always thinking about mobility — they just can’t imagine how a blind person could ever cross the street.”

Butler, who has been legally blind since age 19 (about nine years) can cross the street on his own just fine. But things like adjusting a thermostat or reading a pregnancy test —both situations in which users have engaged Be My Eyes — that’s a challenge.

“When we look at Be My Eyes, it’s an app for all the little things that no one thought about,” he explained. Rather than trying to meld the blind community into a sighted world, Butler said, “Be My Eyes realizes that there’s a gap and tries to address that.”

A Glimpse at a Volunteer

A Glimpse at a Volunteer

Robyn G., a teacher in Florida, was an early Be My Eyes volunteer.

Although none of her relatives need more than eyeglasses, her dog-loving family raised guide-dog puppies when she was a child. As a result, she became familiar with some of the needs of those in the blind community.

She sees her role not as one of a civil servant or altruist but of simply being in the position to offer a valuable service — essentially, “How can I help you today?”

“For somebody who has vision, it seems really mundane,” she explained. “But for somebody who doesn’t have it, it’s an invaluable resource.”

The challenge, as with many nascent tech firms, is how to keep things growing after the initial buy-in. Hauerslev Jensen said his team hopes to offer Be My Eyes as a paid customer-service option to big business.

“Dell [could] have a profile in the app,” he said, giving an example. On the app, hypothetically, “you could check specialized help, select technical, then Dell, and then you can make a call directly to the customer-support system at Dell.” In turn, Be My Eyes could offer the company feedback on improving their support and usability for the blind.

Ya, they might for sure be on to something.